The Problems with Plastics: €16.5 million of taxpayers’ money to dispose of uncollected waste (Part 1)

The disorderly system of handling packaging waste in Slovenia is creating high additional costs and causing significant environmental damage.

Original article in Slovene: Problemi s plastiko: 16,5 milijona davkoplačevalskega denarja za odstranjevanje neprevzete embalaže

Snow-covered, wet piles of waste plastic packaging are being flown around by pigeons, crows, and even seagulls when we visit Snaga, a public utility company based in Ljubljana that manages the drinking water supply, waste waters, and the waste management system, in January 2023.

The waste storage capacity is full, and so the public service provider cannot put this waste anywhere else other than the outdoors.

Jože Gregorič from Snaga estimates that, at the time of our visit in January 2023, approximately 1,500 tonnes of municipal waste in plastic packaging is needing to be picked up.

Snaga collects approximately 400 tonnes (or 33 truckloads) of packaging waste every week into its yellow bins. The collected amount must be temporarily stored, and then forwarded to the packaging-waste management system, in which the packaging is recycled, incinerated for energy use, or disposed of.

By Snaga’s estimate, the largest mass of uncollected packaging waste was at their facilities at the end of 2018 and in the first half of 2019, when more than 4,500 tonnes were waiting for collection.

The collection and removal of packaging waste, which is carried out by public service providers such as Snaga, is financed by citizens through their refuse-collection bills. From then on, the packaging-waste system should be financed by the manufacturers or those who put the packaging on the market. Manufacturers can currently choose from six packaging waste management companies that act as intermediaries to collect packaging waste from municipalities. And those companies are supposed to pick up piles of packaging, which are temporarily stored by public service providers in Slovenia, such as the piles we photographed during our visit to Snaga.

That pile is far from unique.

The problem of uncollected packaging waste has been ongoing in Slovenia for no less than a decade. Thousands of tonnes of packaging have been stored in landfills across the country for so long that the waste has lost most of its potential for recycling. At the same time, these piles are both a hygiene hazard, as rats or cockroaches settle among the food remains in the packaging, and a fire hazard, due to the methane, which is produced during the decomposition of biological residues.

In 2018 and 2020, there was so much uncollected packaging waste that the state ordered the emergency removal of more than 100,000 tonnes of it through intervention laws. Taxpayers footed the bill: they paid € 16.5 million for this.

A producer-funded packaging waste management system in Slovenia was first introduced in 2000. What followed was 20 years of inadequate regulations, legal disputes between the environment ministry and companies that entered the system as intermediaries, as well as a failure to comply with the Court of Audit’s warnings. Currently the law, which is supposed to reorganise the extended producer responsibility system, is under constitutional review.

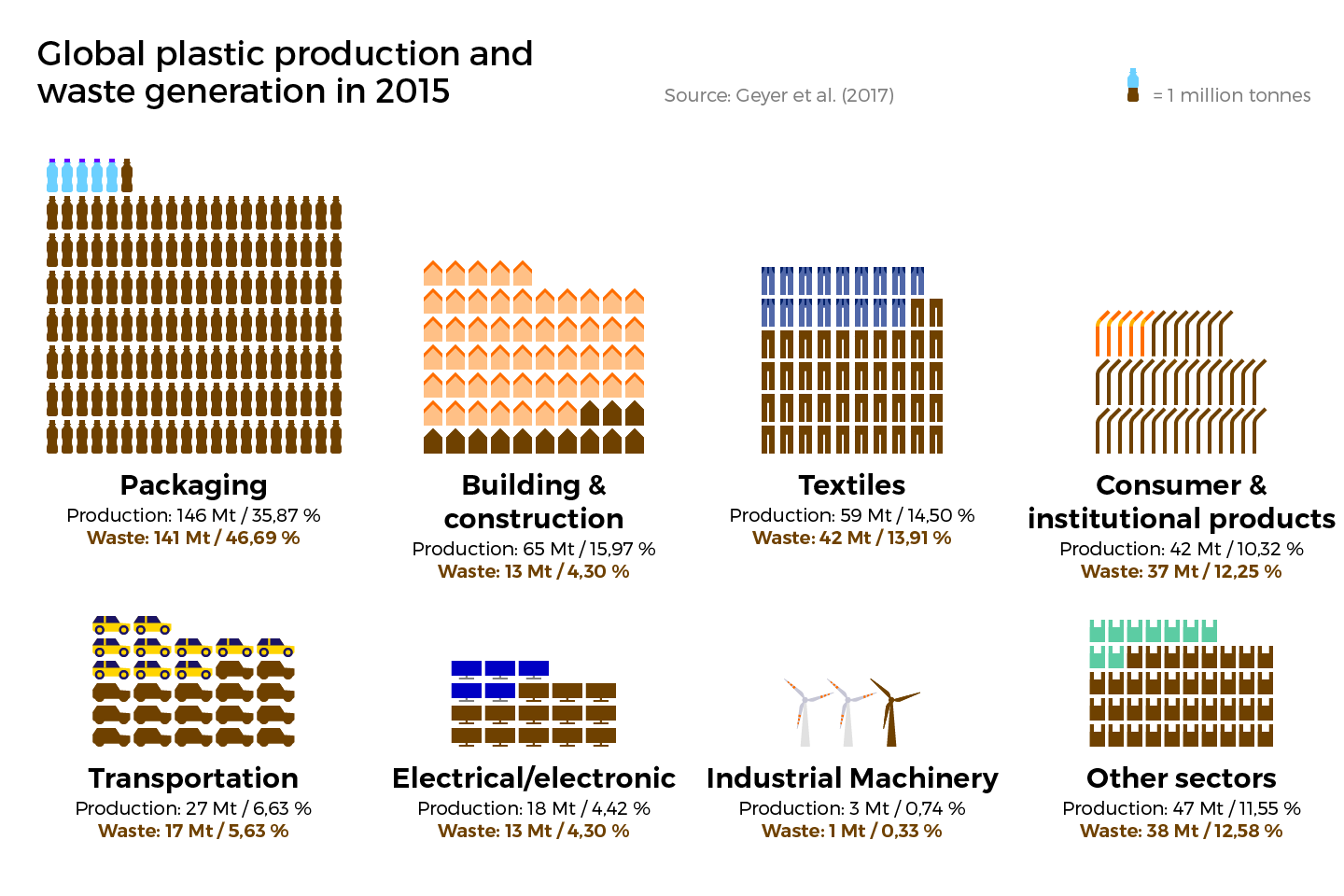

At Pod črto (‘The Bottom Line’), an investigative media outlet, we are publishing an in-depth analysis of system deficiencies in the regulation of packaging-waste management in Slovenia. This is a key problem when it comes to reducing plastic pollution, since it is plastic packaging that represents the largest share of plastic production and plastic waste.

Globally, only 9% of plastic waste is recycled

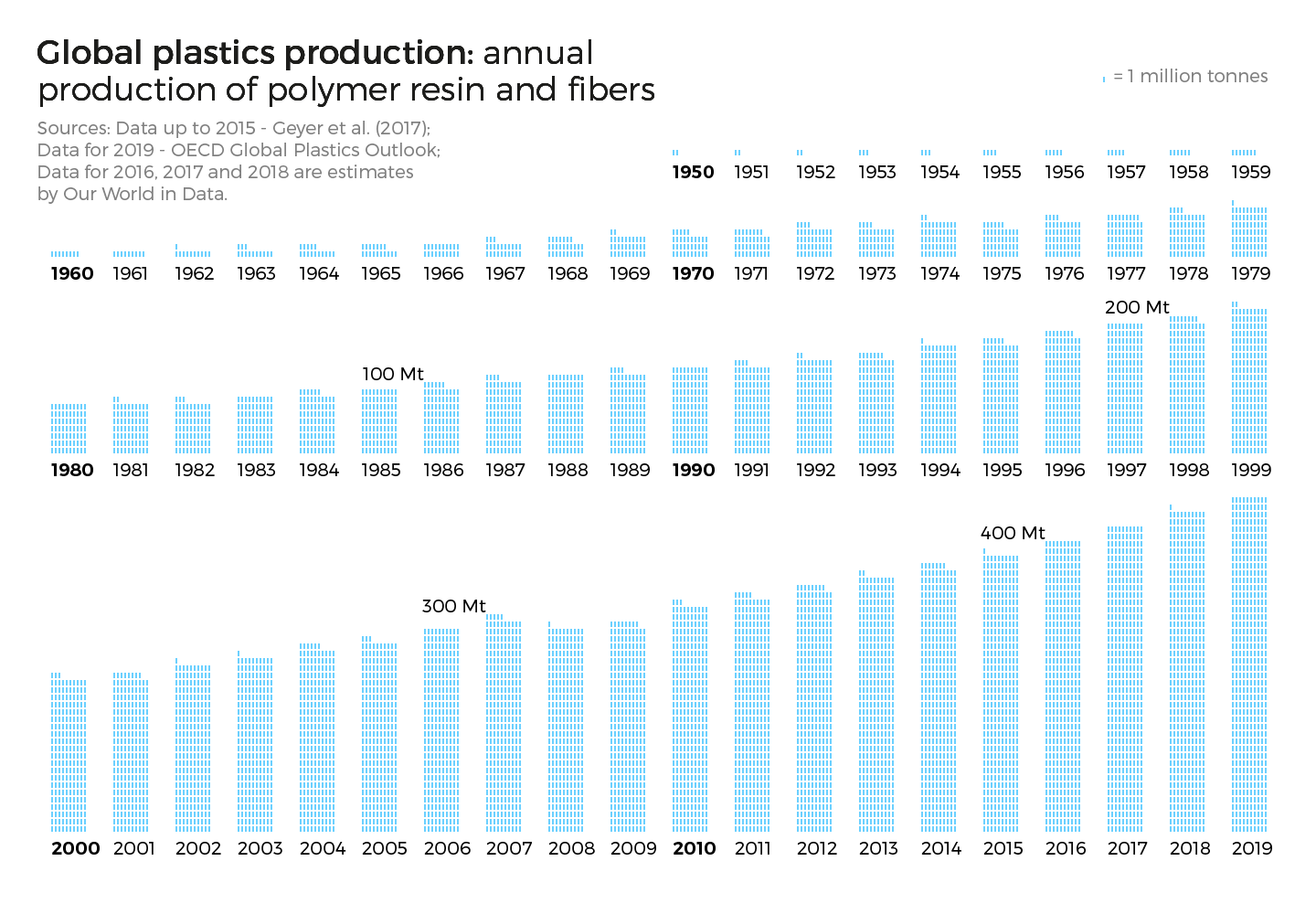

OECD data shows that 460 million tonnes of plastic were produced globally in 2019, which is 230 times more than in 1950. The latest OECD forecasts show that the amount of plastic produced and disposed of will only increase: the mass of plastic waste generated annually will triple by 2060, unless countries introduce serious changes to reverse the trend.

As the amount of plastic produced increases, so does the amount of plastic waste.

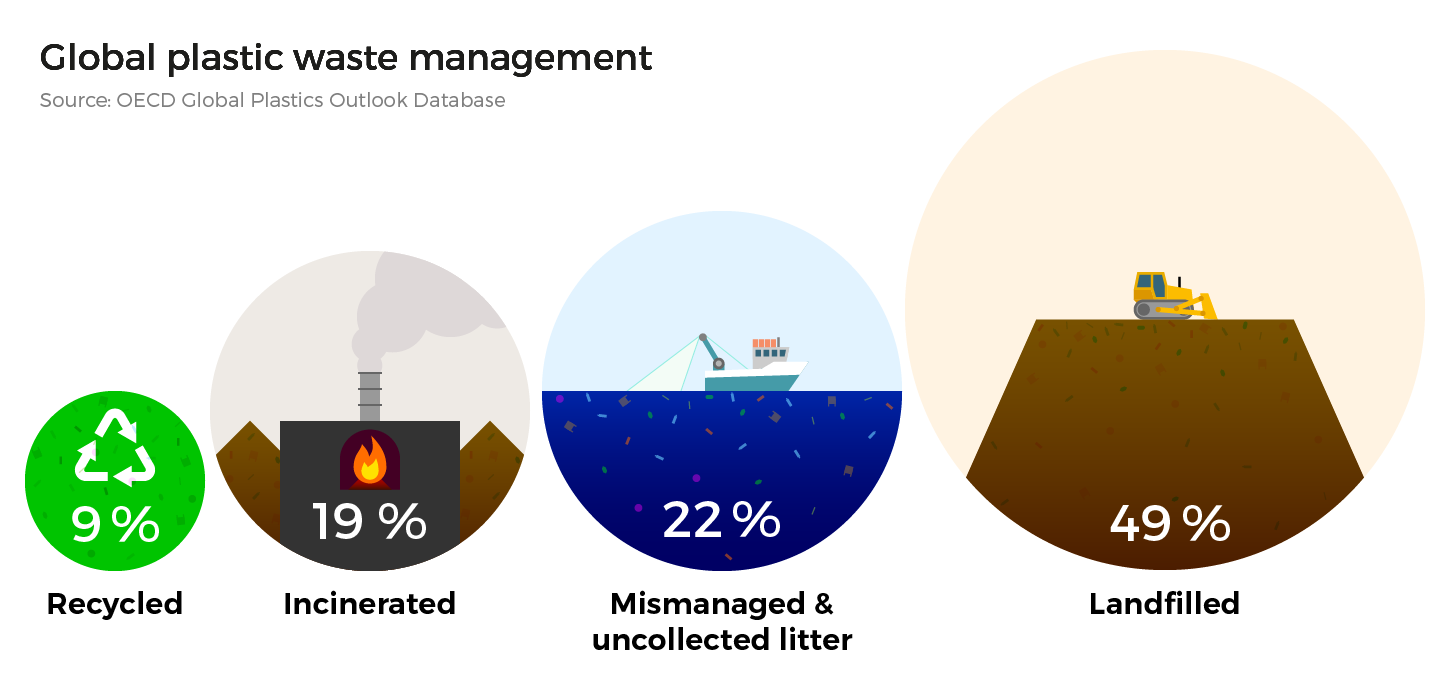

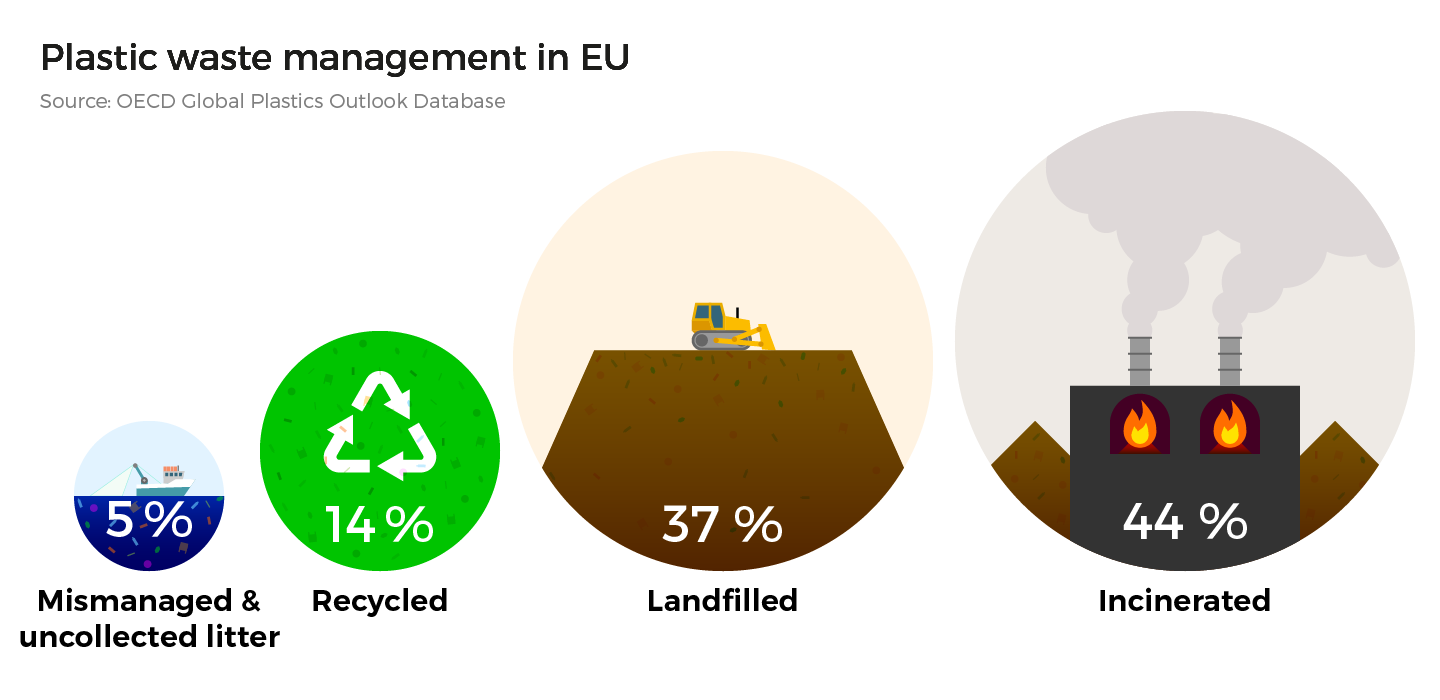

In 2019 only 9% of the 353 million tonnes of plastic waste was recycled. 50% was landfilled, 19% was incinerated, and the remaining 22% evaded waste management altogether and was disposed of in uncontrolled dumpsites, burned in open pits or ended up in terrestrial or aquatic environments. As many as 77.7 million tonnes of plastic was mismanaged or uncollected in 2019 alone, leaving it to leak into the environment where it will be decomposing for hundreds of years.

Most plastic waste is packaging waste, which also has the shortest lifespan and is mostly discarded after single use. Plastic packaging also represents the largest share of plastic in the oceans. In the European Union, plastics account for between 80 and 85% of marine litter, with single-use plastic products accounting for 50% and fishing-related products for 27% of all waste.

Failures of legal regulation

In international law, the issue of plastic waste is mainly regulated within the framework of waste management. There are several legal principles in the international environmental law that apply to waste management. They mostly aim to prevent environmental damage with future generations in mind, and to impose a responsibility for environmental damage on the companies that cause it.

The European Union is a world leader in the field of ecological and sustainable development and waste management. Its many directives in this field oblige member states to achieve certain environmental goals.

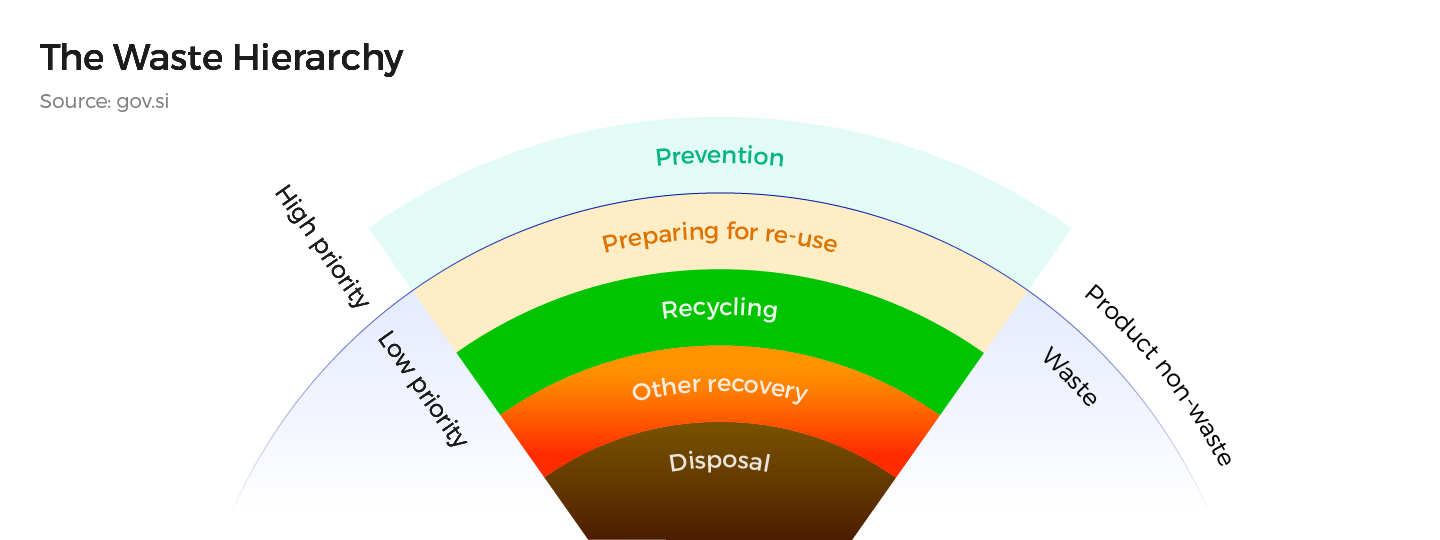

Several directives establish a hierarchy of waste management, on the basis of which member states are supposed to take action. The hierarchy places the prevention of waste first, followed by measures for reuse – and only then recycling and other methods of handling. The EU Directive on Packaging and Packaging Waste also stipulates that countries should implement preventive measures to curb the production of packaging waste.

The waste management hierarchy does not require specific policies from EU member states within certain time limits. It acts more like a non-binding principle according to which the states should formulate measures. Most of the legally binding guidelines regulate the low-priority area of waste management. One of the exceptions is the directive on the reduction of the impact of certain plastic products on the environment, adopted in 2019, which explicitly prohibits certain plastic products and restricts others.

However, the history of directives regulating the low-priority area of waste management, which is the focus of this article, is longer.

One of the more specific environmental goals set by the EU for member states comes from the Directive on Packaging and Packaging Waste, adopted in 1994. The latest goals of this directive, updated in 2018, state that countries must recycle 50% of plastic packaging by the end of 2025, and 55% by the end of 2030.

The directive also stipulates that countries must encourage an increase in the proportion of returnable packaging placed on the market, as well as systems for the reuse of packaging in an environmentally safe manner, which may include deposit schemes, economic incentives, targets, setting minimum percentages of returnable packaging for each type. However, these provisions do not dictate specific measures and deadlines, but only indicate the possibilities of specific policies.

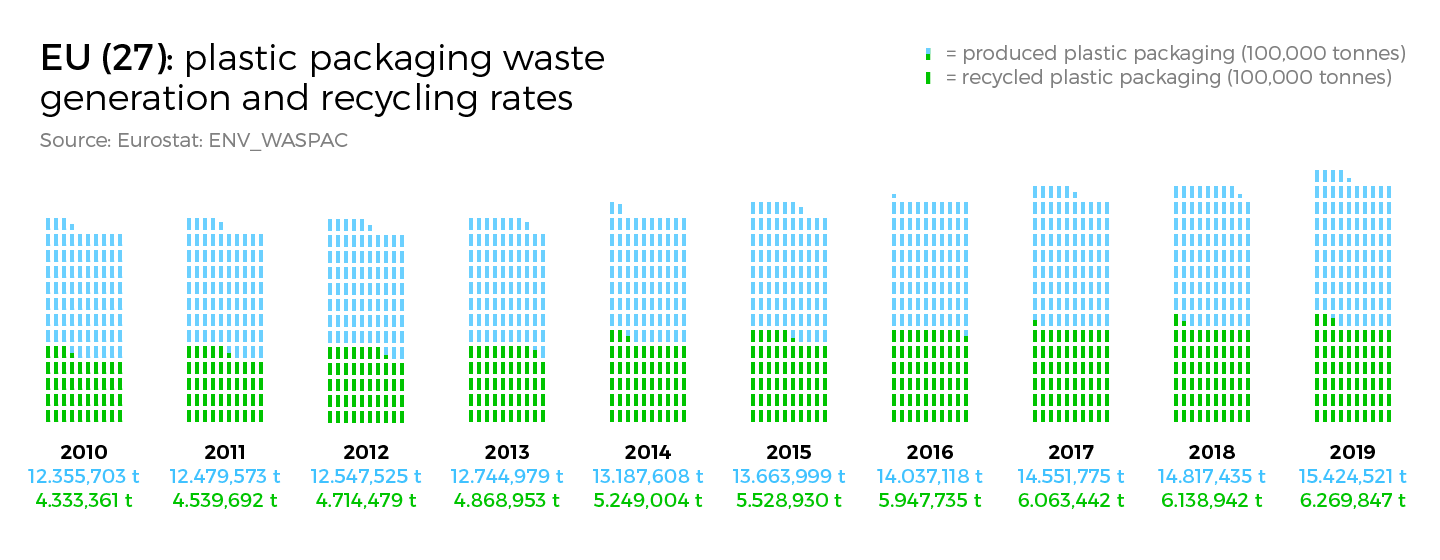

According to Eurostat data, the amount of recycled packaging waste increased between 2010 and 2019. However, the total production of plastic packaging has also increased.

The trend of increasing recycling rates in the European Union is therefore not keeping up with the increase in the amount of plastic packaging placed on the market. While the recycling rate is increasing in accordance with the European directive, the goal of preventing waste generation – which should represent the highest priority according to the hierarchy presented above – is not being met.

In practice, this means that in 2019, the EU-27 countries recycled more tonnes of plastic than in 2010, but paradoxically, despite the growing awareness of the issue, generated more non-recycled plastic waste than in 2010. Waste that is not recycled is either incinerated to obtain energy or disposed of (which can include incineration or landfill).

Slovenia has already transposed regulations on packaging waste from the above-mentioned European directives into legislation, namely with two decrees on packaging waste plus the Environmental Protection Act (of which the third version is currently in force).

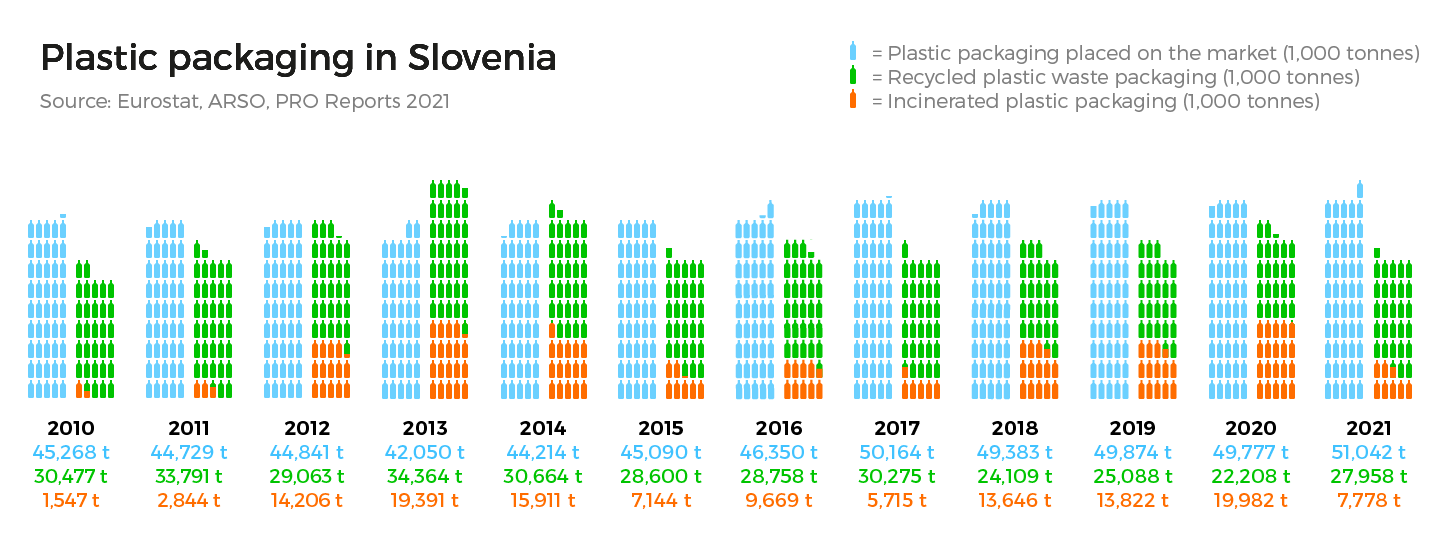

According to official data provided by Slovenia to Eurostat, the amount of plastic waste is also increasing in Slovenia. In 2004, Slovenia produced almost 40,000 tonnes of plastic waste, and in 2019 and 2020, almost 70,000 tonnes each year. Most of this, almost 50,000 tonnes, was plastic packaging.

Since 2013, the production of plastic packaging waste has increased in line with the global trend, while the share of recycled packaging waste has decreased, according to the official data. While in 2013 Slovenia officially put 42,000 tonnes of plastic packaging on the market and recycled more than 80% of this mass, in 2021 the country officially produced 51,000 tonnes and recycled 55%.

We asked ARSO (the Slovenian Environment Agency) why, according to the official data that Slovenia provides in reports to the European Commission, Slovenia recycled as much as 80% of all waste plastic packaging (more than 34,000 tonnes) in 2013, and yet in 2021, the figure had fallen to 55%. This also represents a smaller amount in terms of mass – a little less than 28,000 tonnes.

A spokesperson for ARSO replied, noting that the category of recycling in Slovenian legislation has not changed significantly, but the rules for calculating and verifying the achievement of goals and reporting data have, most recently with the amendment of the European directive in 2019. Before the amendment, only the predominant material in composite packaging was measured and the others neglected. After 2019, each material in composite packaging is measured separately and reported to the Commission. The reduction in the share of recycled plastic packaging may also be partly the result of upgrading the data collection system and introducing new data controls, they added.

Introduction of systems of extended producer responsibility (EPR)

In 2000, in anticipation of joining the EU, Slovenia introduced the“polluter pays” principle – one of the important principles of the European Union law, which shapes environmental legislation in the member states. In connection with waste management, Slovenia now legally enforces the “polluter pays” principle with systems of extended producer responsibility (EPR).

The EPR principle can be applied to different waste streams, such as batteries, electronic waste, tyres, phytopharmaceutical waste and also packaging waste. EPR schemes are set up to ensure that producers bear the financial (and, in some cases, organisational) responsibility for the management of their products in the last stage of their lifecycle – when they turn into waste. All companies that put packaging on the Slovenian market are included in EPR schemes: manufacturers of packaging, suppliers of packaging materials, traders, distributors, packers, and authorised representatives of foreign companies.

Key actors: producer responsibility organisations (PROs)

In Slovenia, we first mandated a packaging management system based on the EPR principle in 2000. It stipulated that those responsible for packaging waste must manage it themselves, or that a producer responsibility organisation (PRO), which has obtained a special environmental permit, must manage the waste on their behalf.

Across most EU member states, EPR schemes are usually established through PROs (financed by the producers). Different countries, however, have developed different models. EPR schemes can be either competitive and non-competitive, while the organisations (PROs) can be either for-profit or non-profit.

The first PRO founded in Slovenia, Slopak, is a non-profit company owned by producers of packaging waste. It was founded by major producers of packaging, such as brewers Pivovarna Laško and Union, dairy company Ljubljanske mlekarne, beverage companies Dana and Radenska, retailer Mercator, and others. The company obtained a PRO environmental permit in 2003. Each producer (also a shareholder) paid up a certain amount to the organisation based on the amount and type of packaging they produced. Slopak’s task was to monitor the amount of packaging waste and hire various subcontractors to handle it.

The legislature mandated that producers must either manage packaging waste themselves, or via a PRO that handles waste for multiple producers.

Shortly after the establishment of the first PRO – Slopak – other, mostly for-profit PROs began to appear. Environmental lawyer Aljoša Petek from Slovenia’s Legal Centre for the Protection of Human Rights and the Environment (PIC, ‘Pravni center za varstvo človekovih pravic in okolja’) commented that the creation of other PROs at the time was possible due to a certain legal loophole. In his opinion, the regulations did not explicitly define that there must only by one PRO. Since then, Slovenia has had an EPR scheme with multiple competitive PROs (some for-profit and some non-profit).

In 2006, when two PROs already existed, the Decree on packaging and packaging waste handling (‘Uredba o ravnanju z embalažo in odpadno embalažo’) was passed into law, regulating the sector until 2021. As per the decree, the conditions for a PRO to start operating was that it first obtain an environmental permit issued from the ministry.

The legal basis for the permit was the second Environmental Protection Act (ZVO-1, ‘Zakon o varstvu okolja’), adopted in 2004. But this law did not explicitly regulate PROs’ permits, nor did it define PROs’ obligation to collect packaging in accordance with the quotas determined by the ministry. This later became the subject of litigation, which is described in more detail below.

Some legal interpretations suggest that ZVO-1 did not define when the PRO’s environmental permit could be revoked. A spokesperson for the ministry explained that revocation is possible under the law, and that the ministry had not received any proposal for revocation from the Natural Resources and Spatial Planning Inspectorate (IRSOP, ‘Inšpektorat Republike Slovenije za okolje in prostor’). They also confirmed that no PRO permit in Slovenia has been rejected or revoked to date.

At the end of 2004, a subsidiary of the Austrian Interseroh Circular Solutions Europe GmbH, Interseroh (today called Interzero), obtained the Slovenian permit. A few years later, the Austrian multinational company was bought by the German ALBA GROUP, under which Interzero still operates today. The PRO Interseroh was the first in Slovenia to implement EPR as part of a for-profit activity.

After 2006, the two existing PROs were joined by new ones. In 2007 and 2009, Ekodin (now Dinos) and Surovina, respectively, obtained permits. Until then, both companies had operated as subcontractors in the packaging-waste management system. Dinos and Surovina are companies where EPR management is vertically connected to the contractors (transporters, sorters, and handlers of packaging waste).

In 2012, the PRO permit was obtained by Recikel, which had been registered three years earlier. Recikel is also vertically connected to subcontractors in the waste management sector (Salomon). In 2013, the company Embakom, which was founded by public utility companies, also obtained the PRO permit. All six companies still operate today.

The problem with packaging waste quotas

When multiple companies operate in the EPR system, each must handle a certain proportion of the packaging waste generated. In 2006, when there were two EPR companies in the packaging waste sector, the ministry prepared new legislation that would regulate how the companies should divide the waste.

In an amendment to the 2006 decree on packaging waste at the end of 2006, a paragraph was added: ‘If the management of municipal packaging waste is regulated by several PROs, the public service provider must ensure that each of the PROs can collect packaging waste based on quotas published by the ministry on its websites.’ The decree prescribed penalties for public service providers if they did not hand over packaging waste in accordance with the quotas, but no penalties for PROs if they did not collect the packaging waste.

The quotas were calculated according to the percentage of packaging producers in each PRO’s EPR scheme. The 2006 decree mandated that, in accordance with these quotas, each PRO should collect packaging waste from each public service provider in Slovenia. Each provider should distribute all the collected packaging among all the PROs according to the quotas determined for that year, and ensure that the PROs could take charge of these quantities. In accordance with this decree, each PRO could collect municipal packaging waste from every public service provider in the country: this would ensure that municipal packaging waste is fairly distributed in terms of type and quantity.

Within such an arrangement, however, complications can arise because there is always more packaging waste collected than officially produced. Namely, if packaging is only measured in weight, municipal packaging waste will always be heavier than when it was put on the market, even if the same amount is in question. This will occur due to biological waste in the packaging, plus water, snow, ice, and so on.

That is not, however, the only reason for the differences in the quantity of produced packaging and the collected packaging waste. A certain legal requirement, in force until 2021, further widened the gap. Until then, producers who put less than 15 tonnes of packaging per year on the market were not mandated to enter EPR schemes.

A decade of legal battles over quotas and a pile-up of waste

The problems with determining and adhering to the packaging-waste quotas began shortly after the adoption of the 2006 decree. Since then, the ministry (Ministry for Environment and Agriculture; later the Ministry of the Environment and Spatial Planning; today the Ministry of the Environment, Climate and Energy) has been headed by as many as 13 different ministers, each of whom was handed a more extensive legacy of legal disputes concerning the determination of packaging waste quotas for each PRO.

In 2006, 2007 and 2008, despite the decree, the ministry did not publish the packaging waste quotas on its websites.

After 2009, the amount of collected municipal packaging waste began to increase, as public service providers began to introduce “door-to-door” collection. The amount of collected waste thus increased precisely in the period when the number of PROs also increased, and when further complications with determining the quotas began.

The ministry declared the packaging-waste quotas for the first time in 2009; and again in 2010 – Slopak should collect 81.1%, Interseroh 18.3%, and Surovina 0.6% of the packaging waste. In 2010, Interseroh filed a lawsuit with the Administrative Court due to the quotas.

This was an outset of more than a decade of legal disputes between the PROs and the ministry. Despite the court’s repeated rulings that there was no legal basis for the packaging-waste quotas, the ministry did not change the law until 2020. The ministry tried to regulate the sector several times by amending the 2006 decree, but new lawsuits piled up until the court ruled in 2018 that PROs were not obliged to collect packaging outside the quantities negotiated with producers in private contracts.

During the litigation period, the problem of non-collection (and subsequent accumulation) of packaging waste escalated annually. The competent authority (inspectorate) had already identified the untimely collection of packaging waste by PROs for the years 2010, 2011 and 2012, but could not take measures due to its limited authority. At the end of 2012, as much as a third of packaging waste remained unclaimed. In 2018, Interseroh obtained a ruling from the Administrative Court, which found that there was no legal basis for determining quotas, so they were not obliged to respect them.

Since the legal ways of forcing PROs to collect packaging waste from municipalities were exhausted, the ministry prepared intervention measures and later the Act Determining Intervention Measures for Municipal Packaging and Grave Candle Waste Management (ZIURKOE, ‘Zakon o interventnih ukrepih pri ravnanju s komunalno odpadno embalažo in z odpadnimi nagrobnimi svečami’), which was adopted at the end of 2018. To resolve the situation, they spent approximately €4.2 million of taxpayers’ money.

According to the rulings issued by the Administrative Court in 2018, the PROs were not legally required to collect packaging waste in accordance with the ministry-issued quotas in 2019 and 2020. At the end of 2020, a record amount of uncollected packaging waste accumulated at public service providers’ sites. According to the data from the Chamber of Public Utilities, almost 53,000 tonnes of packaging waste were left uncollected in 2020 alone.

This left the government no choice but to intervene again. As part of the Act on Intervention Measures to Curb the COVID-19 Epidemic and Mitigate Its Consequences for Citizens and the Economy (ZIUZEOP, ‘Zakon o interventnih ukrepih za zajezitev epidemije COVID-19 in omilitev njenih posledic za državljane in gospodarstvo’), the government financed the disposal of as many as 112 thousand tonnes of municipal packaging waste in 2020, costing the taxpayers an additional €12.3 million.

Towards the end of 2020, the legal definition of EPR was changed in the law (ZVO-1), when a paragraph was added to Article 20 with the provision that the packaging producers or PROs must take care of the collection and handling of all packaging waste generated in Slovenia and included in the EPR system.

In 2021, with the Decree on packaging and packaging waste (‘Uredba o embalaži in odpadni embalaži’), the limit of 15 tonnes of packaging per year for the packaging producers to be required to join EPR was also abolished. Previously, the financial burden of handling packaging waste was transferred from these smaller producers to the ones required to join EPR schemes and subsequently to their PROs. Since 2009, the Court of Audit has repeatedly warned the ministry to remove the 15-tonnes threshold, but it remained in force until 2021.

Due to the new decree, in July 2021, all those who put packaging on the market, regardless of the amount of packaging, entered the EPR system, and PROs began to sign contracts with them. Additionally, with the start of the new year (and thus the new business year) 2022, many packaging producers signed new contracts with PROs, sometimes switching over to a different PRO. Both circumstances together affected the market quotas of individual PROs.

Thus began further quota complications. Due to the methodology that determines quotas for PRO’s collection retrospectively, the market shares were not reflected in the government-determined quotas for packaging collection for most of 2022. As a result, some PROs collected packaging waste at a lower share than the market share.

The methodology for determining quotas was subsequently changed in September 2022. Along with this change, the government also introduced quota equalisation, with the aim of ensuring that the actual contractual obligations with producers were aligned with the obligations to collect packaging waste within the calendar year.

Since the methodology was only changed in September and there was no equalisation until then, the quotas for the fourth quarter were also supplemented with the equalisation of the third quarter. As a result, in some cases a quota higher than 100% was set (the quota for collecting glass was set at 125% for Slopak), and in others it was lower than 0%.

Slopak filed for a constitutional review of the amendment to the decree which changed the methodology. In response to our questions, a spokesperson for Slopak commented that the amendment to the decree was a retroactive change to the operating conditions, and that the company was assigned obligations in the fourth quarter that significantly exceeded its ability to collect the waste in accordance with its existing contracts.

But the Constitutional Court rejected the initiative in January 2023. A Slopak spokesperson commented that the company respects the legal order and, upon receipt and finality of the procedural decision of the Constitutional Court, will comply with all legally binding decisions and collect any amount of waste not collected in the last quarter of 2022.

It is not yet clear whether the amendment to the Environmental Protection Act and the 2021 decree were sufficient to establish the legal basis for the quota collection as determined by the government. At the ministry, they believe that the legal basis is regulated sufficiently, and are taking action against PROs who didn’t collect enough in cooperation with the inspectorate.

In 2021 and 2022, according to the assessment of the Chamber of Public Utilities, there was significantly less mixed packaging waste left unclaimed compared to 2020: in 2021, 8,000 tonnes; in 2022, 5,700 tonnes.

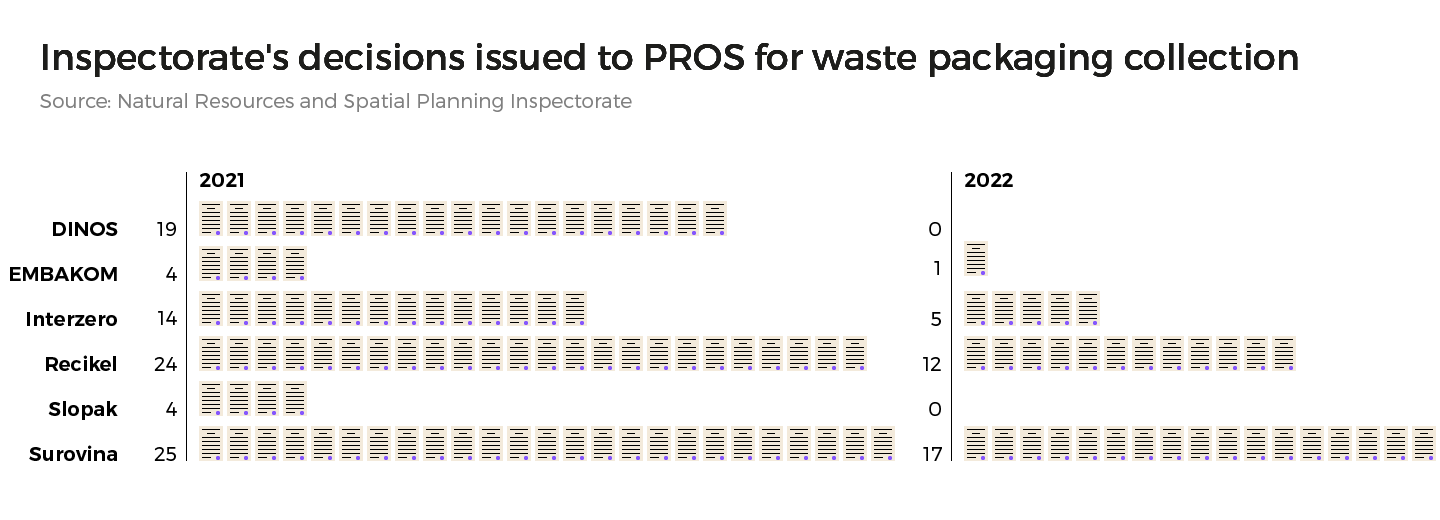

Tanja Bolte, Acting Director of the Environment Directorate at the Ministry of the Environment, Climate and Energy told us that in September 2022, “when the packaging waste was repeatedly uncollected, we sent a clear message that we would not be issuing any new intervention measures; the state would not give its own or taxpayers’ money to fulfil the PROs’ duties. That is why we created additional activities with the Inspectorate to push PROs to collect the unclaimed packaging waste.”

But several PROs appealed the inspectorate’s decisions again. Indeed, the majority of the decisions were appealed, according to the inspectorate. All PROs except Embakom, which refused to comment, also confirmed to Pod črto that they appealed against all decisions. It is not yet clear whether the court will decide that the amended Environmental Protection Act (ZVO-1) and the new decree are able to properly and legally regulate PROs’ obligations to collect the entire amount of packaging produced in Slovenia.

The ministry-issued permits for PROs, which are also the subject of legal disputes between the ministry and some PROs, thus presenting another setback. Only two PROs, Embakom and Surovina, have legally valid permits aligned with the latest decree on packaging waste. Other PROs appealed against the new permits issued in 2021. The Administrative Court cancelled the new permits, so certain PROs are still operating with older permits, obliging them to the regulations of the 2006 decree, in which, for example, the threshold of 15 tonnes has not yet been removed.

Representatives of four PROs agree that the new regulations were a step in the right direction. At Recikel, they stated that since the regulatory changes in September 2022, the quotas are determined appropriately and they have been fulfilling their obligations accordingly since then. Spokespeople from both Dinos and Surovina pointed out that they had collected all of the waste according to the 2022 quotas. At Slopak, they believe the quota framework is still not adequately regulated. At Interzero, they welcome the abolition of the 15-tonne annual limit for inclusion of packaging producers into EPR, but they believe the entire system still lacks transparency.

In a statement, Tanja Bolte from the Environmental Directorate told us they hoped the court will confirm that the legal basis for the quotas is finally adequately regulated. She pointed out they are still waiting for the Constitutional Court’s ruling on the third Environmental Protection Act (ZVO-2), passed in 2021. Depending on the ruling, the new legislation could significantly transform the entire EPR framework in Slovenia.

Our forthcoming articles will discuss the constitutional review in detail. Notwithstanding, Bolte has announced that following the decision of the Constitutional Court, the EPR system would undergo significant reforms.

The environmental toll of unclaimed packaging

In 2018 and 2020, the state financed the collection and handling of 112.4 thousand tonnes of packaging waste using €16.5 million of taxpayers’ money. But what actually happened to the collected packaging?

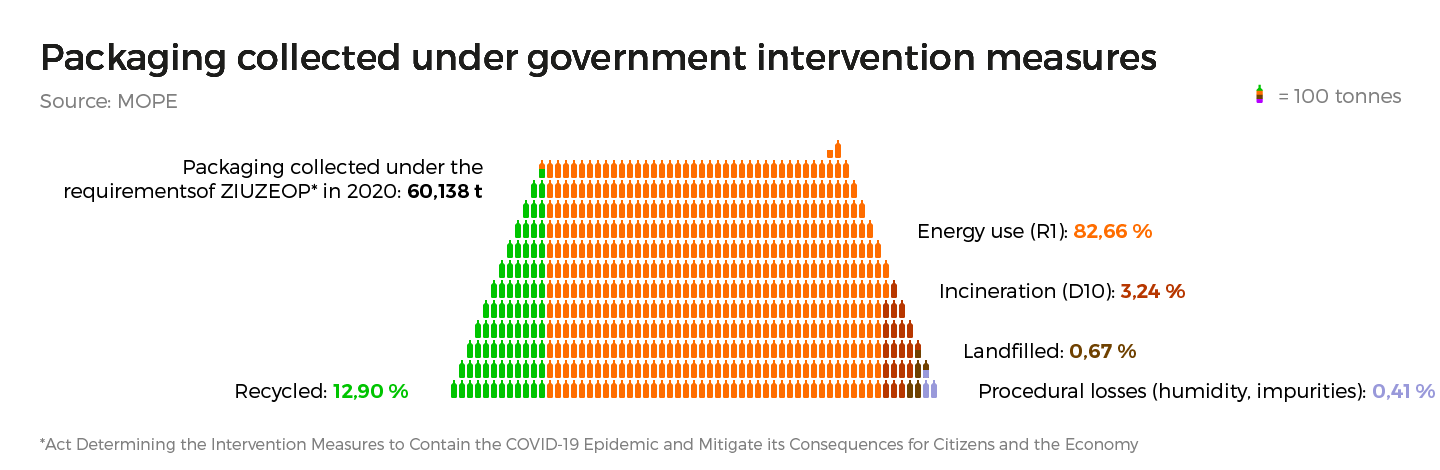

The ministry did not send data on the packaging collected before 2020, but they did provide information on the packaging waste removed by the government in 2020 (about half of the total packaging removed by intervention). More than 85% of this packaging waste was incinerated, mostly for energy recuperation and some for disposal. Only 12.9% was recycled.

Municipal packaging waste is generally less suitable for recycling than non-municipal packaging, due to all the impurities it contains (foreign matter of other waste, a common biological component). But when piles of waste lie in the open for a long time, their potential for recycling is lost even further.

The longer the packaging waste lies in unsuitable storage (or even in suitable storage), the greater a hygiene and fire hazard it represents, and the less suitable it is for recycling.

As Sebastijan Zupanc, director of the Chamber of Public Utilities, explained to us: “Packaging that is stored outdoors for a long time begins to disintegrate due to the effects of the weather and sunlight, and the recyclability of the materials decreases. Cockroaches, other insects, and rodents also settle in it, which quickly makes it unsuitable for sorting. Such packaging poses a sanitary, health and fire hazard. If cockroach-infested packaging is placed on the sorting line for processing, the entire sorting facility (flowing belts, separators, storage bins, etc.) becomes infected with cockroaches, which can only be removed by weeks-long periods of disinfection. That is why, as a rule, such packaging waste is mostly simply ground up and submitted for incineration.”

In short, packaging waste left uncollected for long periods usually ends up in flames. Our data confirms that is indeed what happened to the majority of the thousands of tonnes of waste removed with public funds under intervention measures in 2020.

In a statement to Pod črto, the ministry commented: “Since the storage capacities of public service providers were full, they were forced to store waste outside of the designated storage areas, which greatly affected the suitability of the collected municipal packaging waste for recycling. The packaging was contaminated with food and drink residues, and the decay of these residues is accelerated outdoors. The decaying waste starts to attract rodents and insects. Large amounts of municipal packaging waste also present a fire hazard.”

As the packaging waste was left to decay for a long time, most of it ended up in the incinerator. Waste incineration, however, poses significant risks to the environment and health, warns Jaka Kranjc from Ecologist Without Borders (‘Ekologi brez meja’).

“Due to the thermal processing of packaging, many pollutants end up in the air. With plastic waste, impurities such as dyes or elasticity enhancers are particularly dangerous,” explains Kranjc. “Then,” he continues, “the pollutants, because they mostly consist of durable molecules that reach the soil and plants through precipitation and deposition, and can ultimately end up in our food via food chains. Another aspect is that the waste never burns completely. Ash remains, partly on the filter and partly on the furnace itself. The ash contains heavy metals, one example being mercury. If we don’t handle the ash properly, hazardous substances can leak into the environment again.”

A decade of neglect in this sector cost us more than €16 million and caused unnecessary environmental damage. Along with all this, the quota determination is not even the only systemic problem of packaging waste management.

Following the latest amendment to the European Directive on Packaging and Packaging Waste, in Slovenia, most of the costs covered by citizens through municipal bills should have already been transferred to producers. This has not yet been done, which means Slovenia now risks EU penalties. Meanwhile, the entire sector is waiting for the ruling of the Constitutional Court, which will decide on the constitutionality of the EPR reform presented in the latest Environmental Protection Act (ZVO-2, ‘Zakon o varstvu okolja’). You will learn more about this in our next article on the topic of problems with plastic.

The Problem with Plastics investigation was created within the framework of the European Data Journalism Network (EDJNet), an international project, which is co-financed by the European Commission between April 2021 and March 2023.

Nastanek tega članka ste omogočili bralci z donacijami. Podpri Pod črto

Deli zgodbo 0 komentarjev

0 komentarjev