Fine particles in the air: Ljubljana among the most polluted European cities

Fine particle pollution causes premature births, illness, and, in Slovenia, more than 800 preventable deaths every year.

Original article in Slovene: Fini delci v zraku: V Sloveniji bomo morali onesnaženost znižati za dve tretjini

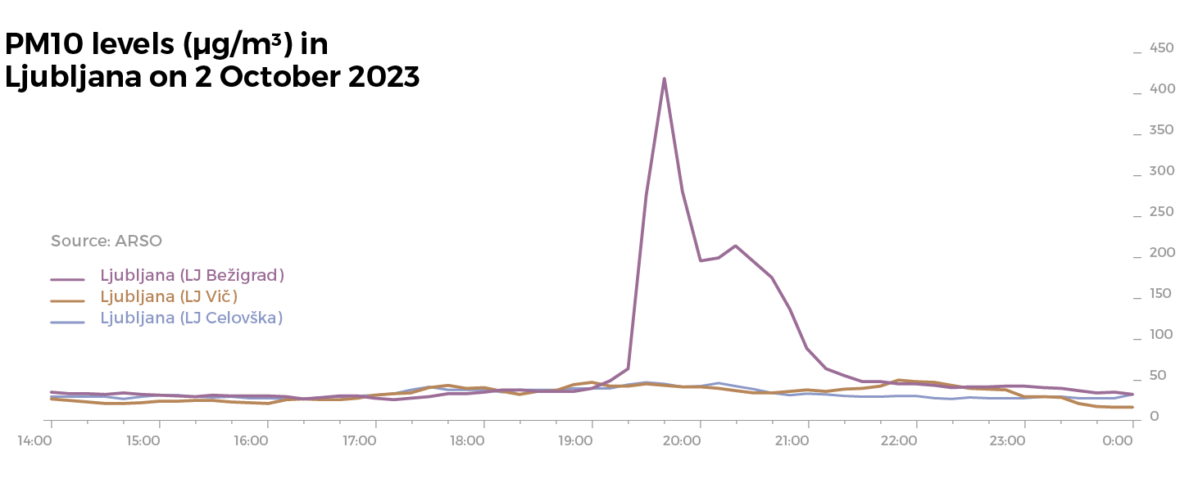

On the first Monday in October last year, the centre of Ljubljana, Slovenia’s capital, was lit up by fireworks and burning torches. According to one of Slovenia’s main media outlets, RTV Slovenija, football fans used around 100 rockets and numerous smoke bombs in what is believed to have been the biggest pyrotechnic event in Slovenia to date.

The next day, the Slovenian Environment Agency (ARSO), which monitors air pollution throughout Slovenia, released data from airborne particulate matter monitoring sites in Ljubljana. The data show that PM10 air pollution in the capital rose tenfold in just 40 minutes that evening, from the usual 40 to over 400 micrograms per cubic metre of air. According to ARSO warnings, particulate matter levels were even higher in the immediate vicinity of the fireworks display, as their monitoring sites are located away from the city’s venues.

Even short-term exposure to particle-laden air can be harmful to health. However, it is even more problematic that exposure to air pollution is chronic in Europe, especially in European cities. The European Environment Agency estimates that nearly 240,000 people die each year in Europe as a result of fine particulate air pollution.

Particulate matter, or abbreviated to PM, is a type of air pollutant that is suspended in the air in liquid or gaseous form. Particle concentrations are measured in micrograms per cubic metre of air (µg/m³).

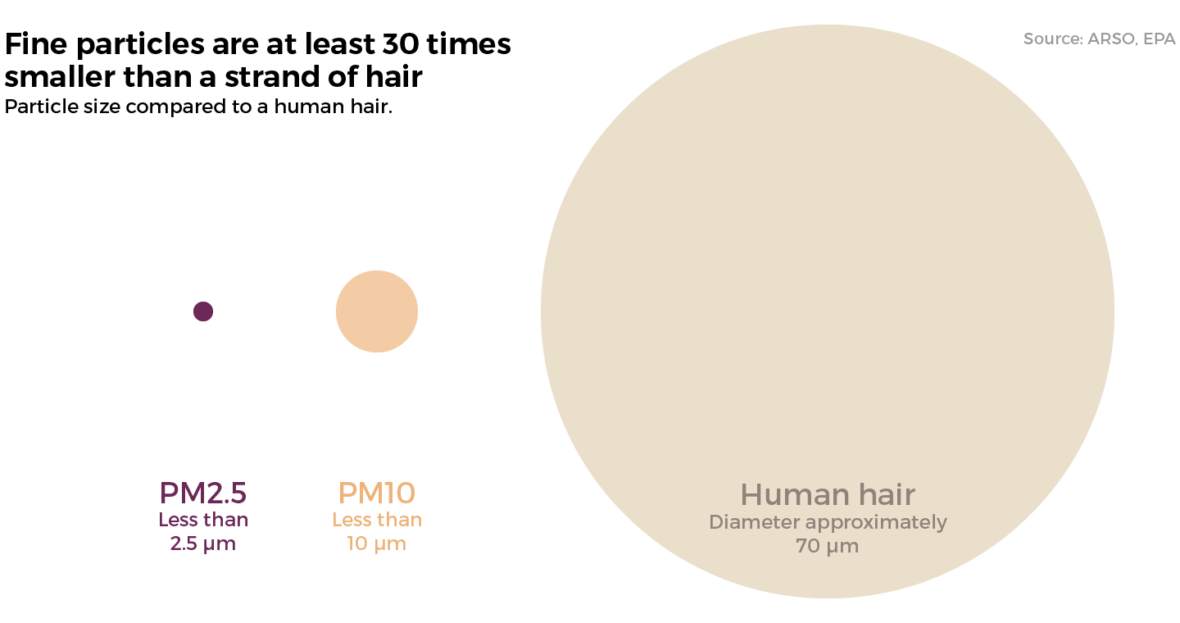

Particles are classified according to their size or aerodynamic diameter, which is measured in micrometres (μm). Those with a diameter of less than 10 μm are referred to as PM10. Those with a diameter of less than 2.5 μm are referred to as PM2.5.

PM10 particles also include PM2.5 particles.

Air pollutants that increase mortality include nitrogen oxides, ozone, carbon monoxide and sulphur dioxides. However, the effects of exposure to particulate matter (both PM10 and PM2.5), especially fine particulate matter (PM2.5), are the most studied and are used as a surrogate indicator of air pollution in general. “The size [of particles] mainly affects the passage of smaller particles through the cell membrane directly into the bloodstream, thus spreading with the blood throughout the body and having a harmful effect in most body tissues,” wrote Simona Perčič, a public health specialist at Slovenia’s National Institute of Public Health (NIJZ), in her response to us. That is why we are focusing on PM2.5 pollution in this article.

The diameter of a PM2.5 particle is at least 30 times smaller than the diameter of an average human hair, making it invisible to the naked eye.

PM2.5 particles are known as fine particulate matter.

Ljubljana is one of the most polluted cities in Europe in terms of fine particulate matter

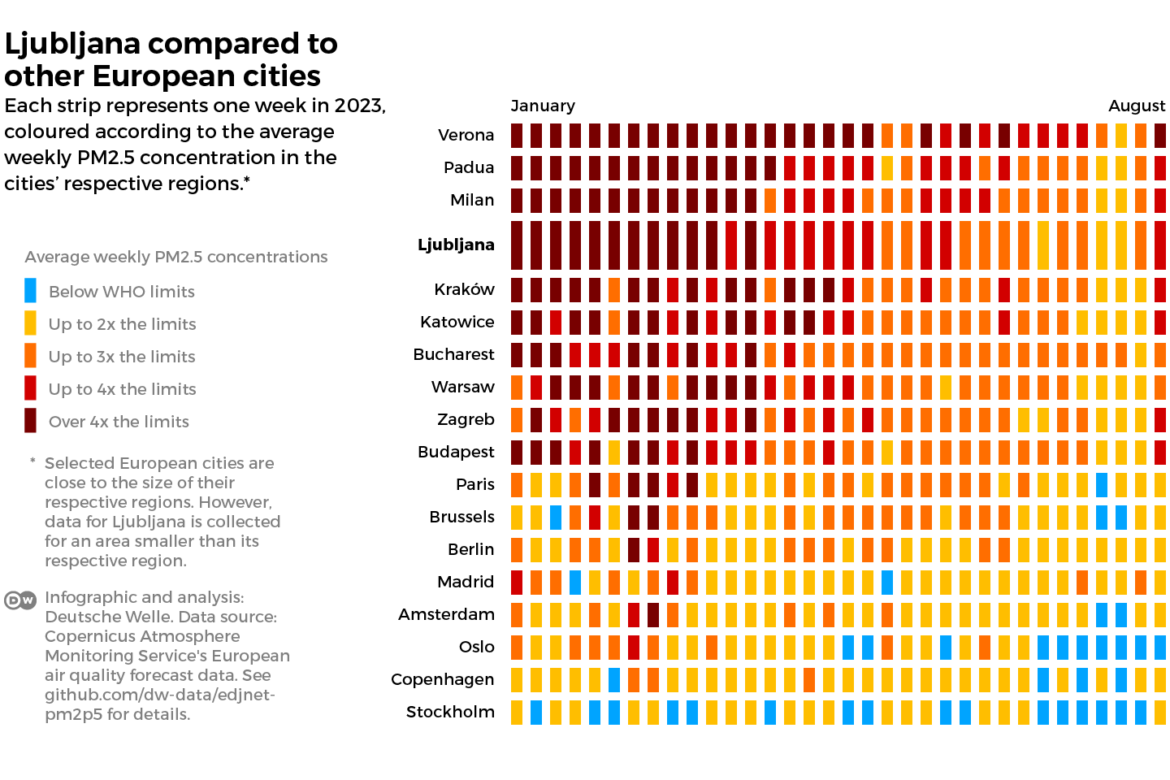

In 2022, 98% of Europe’s population lived in areas with particulate matter concentrations above the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) recommendations, according to an air quality investigation published in early September last year by our partner organisation Deutsche Welle, as part of the European Data Journalism Network (EDJNet) project, of which Pod črto is a member. The analysis used data from the Copernicus Atmospheric Monitoring Service.

The Guardian came to similar conclusions about air pollution in Europe, using a dataset compiled by researchers at the University of Utrecht and the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute (TPH) to graphically depict air quality in 2019.

According to Deutsche Welle, the situation is worst in cities which are home to over 70% of Europe’s population. For this reason, they took a selection of European cities and analysed satellite measurements of fine particulate matter at the level of the region in which the major cities are located. For the Slovenian capital, Ljubljana, they selected a narrower relevant area, allowing us to compare it with other major cities.

We found that fine particulate levels in Ljubljana are similar to those in the most polluted European cities – Ljubljana is just behind Verona, Padua, and Milan. In terms of pollution, the winter months are the most problematic.

Ljubljana is among the European cities where around 9% of deaths in 2015 were attributable to fine particle pollution, according to the authors of a study published in Lancet Planetary Health. This is partly due to poorer ventilation, as according to ARSO, the average annual wind strength in Ljubljana is three times weaker than in Vienna, which is among the European cities where around 7% of deaths in 2015 were attributable to fine particle pollution.

“Particles of different sizes most often enter the body through the respiratory tract, where oxidative stress and inflammation are triggered, and the increased respiratory responsiveness is most often reflected in coughing and difficult breathing, if there are any associated diseases,” explained Dr Andreja Kukec from the Faculty of Medicine, University of Ljubljana.

The effects of particles on human health depend on the size and chemical composition of the particles: those larger than 10 μm are trapped in the upper respiratory tract, nose, and nasal cavities. “Smaller particles, i.e., those smaller than 10 μm, can also reach the lower respiratory tract, whereas even smaller particles, i.e., those smaller than 2.5 μm, penetrate the pulmonary alveoli,” said Dr Kukec.

The fatal diseases considered by the World Health Organisation (WHO) to be attributable to fine particle pollution in calculating indicators are ischaemic heart disease, stroke, lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and acute lower respiratory tract infections.

In Europe, we breathe more polluted air than we think

To limit the effects of air pollution on human health, the WHO recommends limit values for concentrations of certain pollutants, including fine particles. A limit value is a level of particulate matter concentration, determined on the basis of scientific evidence, that must be achieved within a specified time and not exceeded once achieved.

Current WHO recommendations from 2021 require that the daily average level of fine particulate matter should not exceed 15 µg/m³ and the average level over a calendar year should not exceed 5 µg/m³. However, these recommendations are not currently legislated at the European Union level.

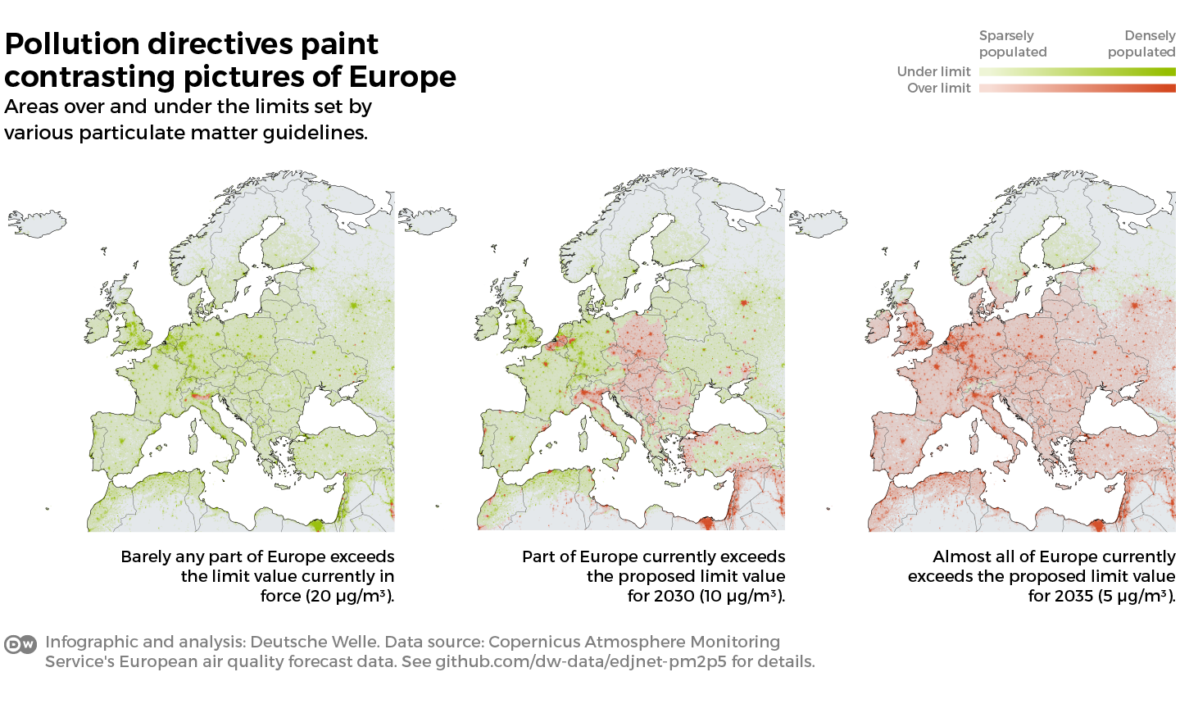

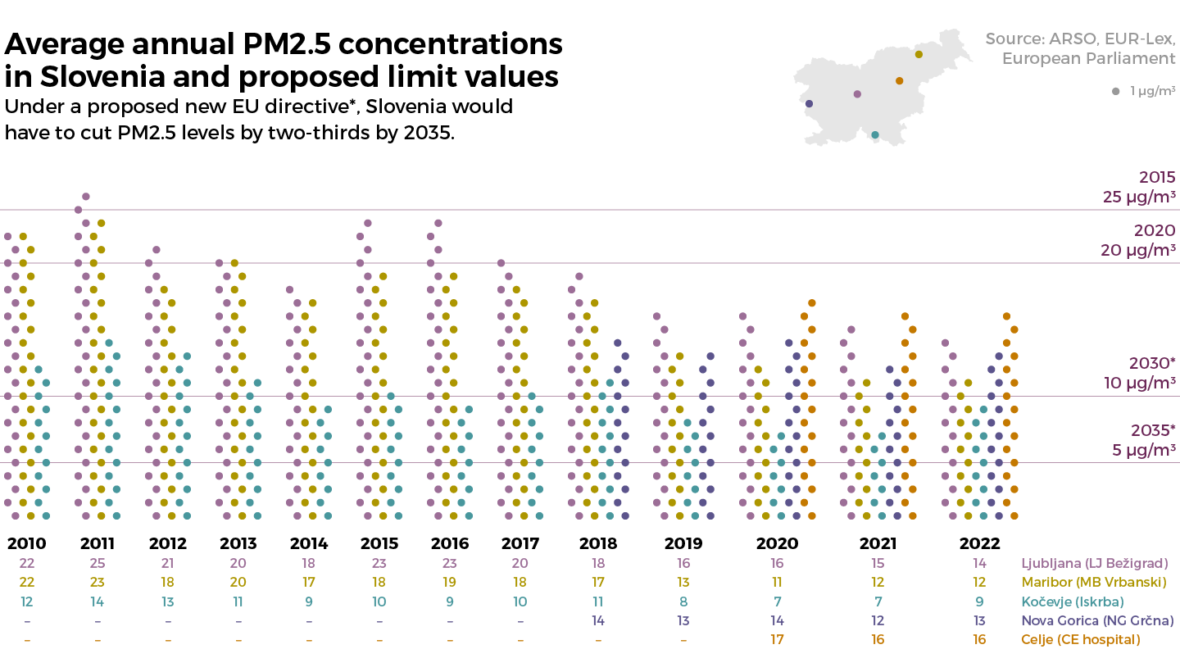

The annual average limit value for fine particulate matter in the European Union, including Slovenia, is currently set at 20 µg/m³, which is four times as high as the WHO recommendation.

In mid-September last year, a few days after the Deutsche Welle analysis was published, the European Parliament considered the proposal for a new EU directive on air quality in Europe.

In the new ambient air quality directive for Europe, the European Commission has proposed an annual average limit value of 10 µg/m³, which Member States would have to implement by 2030. The European Parliament added a proposal that would require Member States to implement a limit value of 5 µg/m³ by 2035, as also proposed by the WHO. At the end of January this year, we were informed by the European Parliament that the proposal would be subject to months of trilogue between the European Commission, the European Parliament, and the European Council.

The proposed limit value for 2035, which follows current WHO recommendations, is currently exceeded by virtually the whole of Europe. As a result, most Europeans currently breathe air that is more polluted than the WHO considers safe for human health.

More than 800 people die each year in Slovenia from fine particulate air pollution

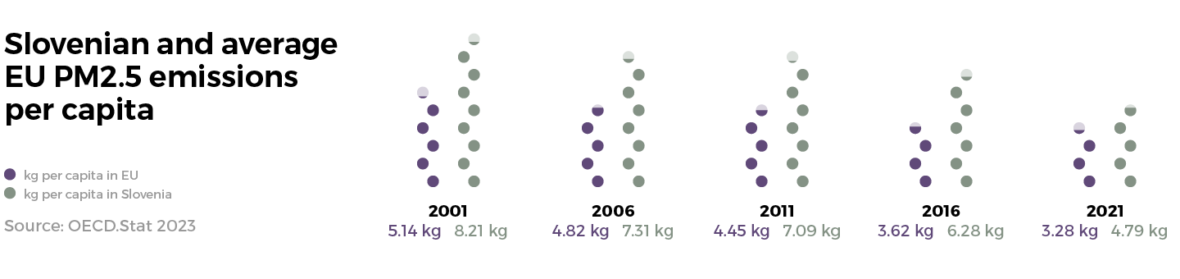

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Slovenia’s per capita fine particulate matter emissions have been above the European Union (EU) average for decades.

Although fine particulate matter emissions per capita are slowly decreasing, Slovenia is still “among the European Union countries with the most polluted air and and the highest particulate matter emissions per capita and per unit area,” ARSO confirmed in a written response.

Epidemiological studies have shown that particulate matter influences the development and aggravation of respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, some neurological diseases, and type 2 diabetes. “In particular, over the last decade, researchers have focused on adverse outcomes during pregnancy, such as premature birth, and the associated low birth weight, which can also affect the quality of life in later life,” Dr Kukec pointed out.

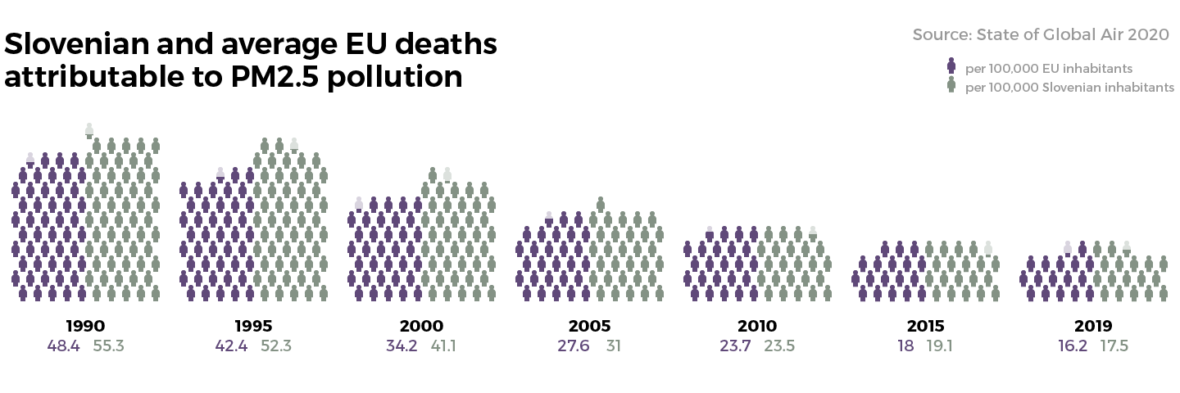

Deaths due to particle pollution have also declined in recent decades. However, in Slovenia, the mortality rate due to fine particulate air pollution is still higher than the average for European Union countries.

According to the US-based Health Effects Institute (HEI), 823 deaths could be prevented in Slovenia in 2019 if fine particulate air pollution were eliminated.

Fine particulate matter concentrations well above recommendations at most monitoring sites in Slovenia

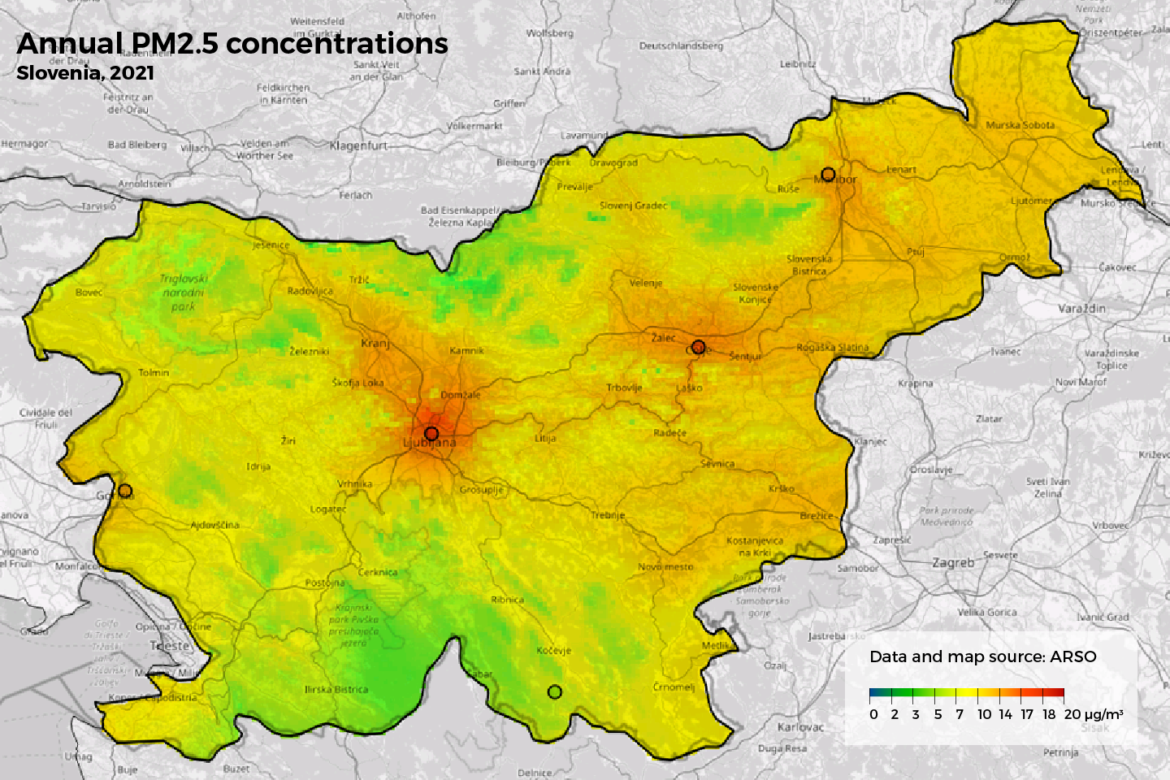

At present, Slovenia does not exceed the current limit of 20 µg/m³ for annual average concentrations of fine particulate matter, but levels are approaching it in many places – the three largest Slovenian cities, Ljubljana, Maribor and Celje, are critical areas. The lowest concentrations were recorded at the Iskrba monitoring site in a rural area. However, “even levels below the current legislative limit pose a health risk,” warns ARSO in its report, Air Quality in Slovenia in 2021.

“According to the proposed new directive (if it were already in force), the annual limit value for PM2.5 for would be exceeded at all urban monitoring sites in Slovenia, and the limit value for PM10 would be exceeded at most urban monitoring sites,” ARSO wrote in its response.

In Slovenia, according to ARSO, the annual mean concentrations of fine particulate matter at individual monitoring sites in 2022 range from 9 to 16 µg/m³. These are fine particulate matter concentrations that exceed the WHO recommendations by a factor of 3 or more.

The new annual limit values for fine particulate matter, to be achieved by 2030 and 2035 respectively, are currently exceeded at virtually all monitoring sites.

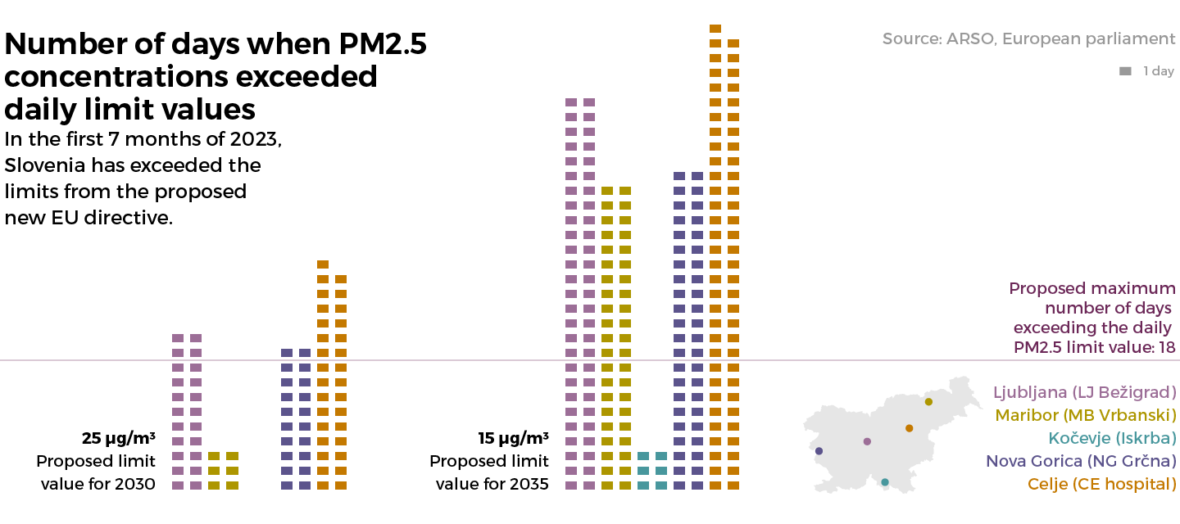

Under the proposed directive, as amended by the European Parliament, by 2030, the average daily level of fine particulate matter should not exceed 25 µg/m³ on more than 18 days per year. By 2035, the daily limit would be reduced to 15 µg/m³. In 2023, by the end of July, the proposed daily limit value of 15 µg/m³ was exceeded most frequently in Celje, i.e., 63 times.

Fine particulate air pollution poses a particular risk to population groups such as pregnant women, babies and children, the elderly, and the chronically ill. “Last but not least, taking into account demographic indicators, people with a lower socio-economic status are also affected,” Dr Kukec added.

It is therefore also worrying that for the last three years in a row, the highest annual level of fine particles has been measured at a monitoring site located near the Celje General Hospital.

The NIJZ recommends that institutions such as nursing homes, kindergartens, schools, and hospitals, whose occupants are vulnerable to particulate pollution, ventilate at times when particulate matter concentrations are falling. It also recommends that such facilities be built in non-polluted areas.

“Although the staff try to follow the recommendations, it is sometimes necessary to ventilate the rooms even when the concentration of particles is higher,” the Celje hospital explained. A ventilation system is only in place in the new replacement building, and not in the older part of the hospital.

The NIJZ guidelines on ventilation and outings for children in kindergartens and schools are also “only partially feasible in practice, and from the point of view of indoor air pollution, they are also double-edged where there are large numbers of children, because we know that rooms with large numbers of people need to be ventilated as often as possible in order to ‘purify’ the air in the rooms microbiologically”, replied Renata Rom Mrcina, Nutrition and health-hygiene supervisor at the Jelka childcare centre. The kindergarten is located in Ljubljana’s Bežigrad district, which is second only to Celje in terms of concentrations.

So how can a reduction in fine particulate pollution be achieved? “In Slovenia, due to its varied terrain and location on the lee side of the Alps, the conditions for reducing air pollution are often poor, especially in winter,” ARSO told us, adding that to reduce particulate matter in the air, “emissions need to be reduced, as we have no influence on the geographical location or the weather”.

Domestic wood burning as the main source of fine particulate matter emissions

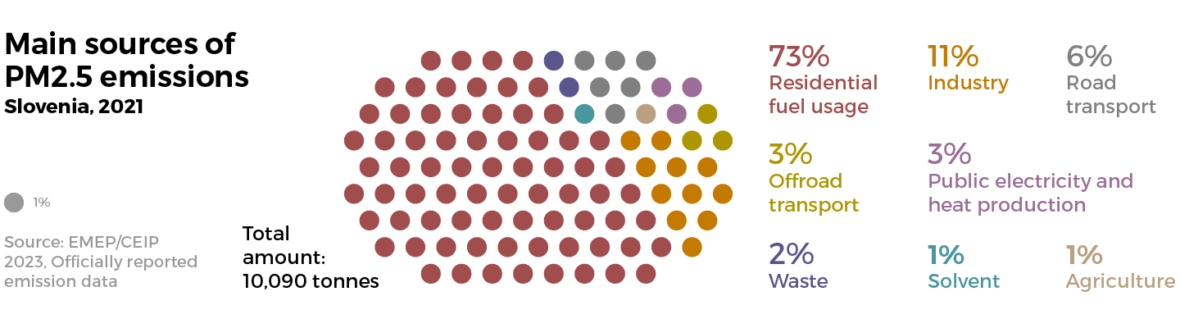

Based on data from the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), Pod črto has identified the main sources of fine particulate matter emissions in Slovenia. By far the largest share of fine particulate matter emissions comes from household fuel use, especially wood burning.

This is followed by industrial emissions and road transport by a wide margin.

A more detailed breakdown of household fuel use shows that although wood fuels account for 39% of all fuels consumed by households in 2021, small wood-burning appliances contribute more than 99% of the particulate emissions from household fuel use.

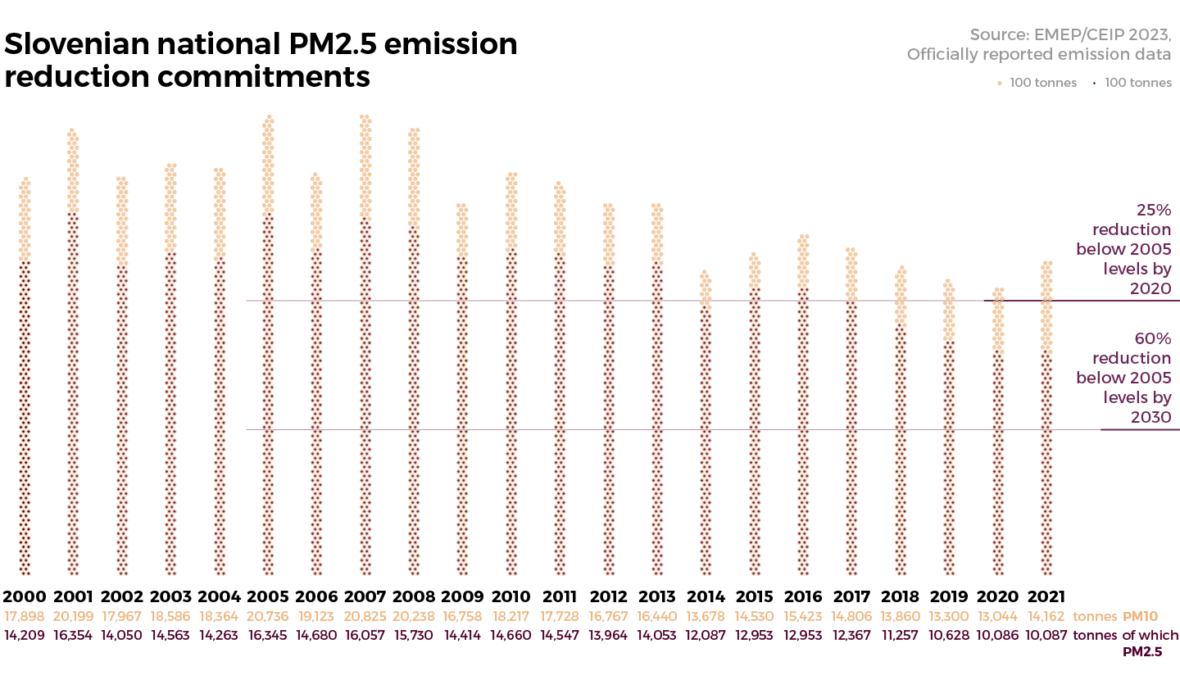

EU countries are required to gradually reduce fine particulate matter emissions on an annual basis, and so far, Slovenia is on track. By 2020, it was committed to reducing fine fine particulate matter emissions by 25% compared to 2005 levels, but there is a new commitment for 2030: by then, Slovenia must have reduced fine particulate matter emissions by 60% compared to 2005 levels, i.e., by an additional 3.5 thousand tonnes compared to 2021.

Over the decades, the modernisation of small combustion plants or their replacement by gas burning devices or ambient heat (heat pumps) has contributed to lower fine particulate emissions in Slovenia, as have warmer winters. However, in some places, emissions partly increased during the recession, when households increased their consumption of biomass due to cheaper prices.

In Slovenia, measures related to wood combustion are split between conflicting objectives, as there are several aspects to the use of wood fuel. From the point of view of public health, it is a source of pollution that the state controls and limits, while on the other hand it is a renewable source of energy that the state uses to replace the use of fossil fuels where district heating is not possible. At the same time, wood combustion is recognised as a reliable and competitive energy source, which gives Slovenia a comparative advantage as a forested country.

A new National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP) for Slovenia is currently being drafted, but according to an assessment by the Climate Action Network (CAN) Europe in October last year, it is not ambitious enough in terms of targets for reducing energy consumption and increasing the share of renewable energy sources. Last December, the European Commission also gave its assessment of EU Member States’ draft NECPs. For Croatia, Denmark, France, Germany, Lithuania, and the Netherlands, it found that they more or less comprehensively addressed all other sources of emissions in addition to CO2. For Slovenia, Estonia, Hungary, and Romania, however, it concluded that additional measures should be planned to reduce other emissions in a timely manner.

In response to criticism that the NECP is not ambitious enough, the Ministry of the Environment replied that while there is a great potential for renewable hydropower in Slovenia, it is located in protected areas where the risks to nature and health are very high. The possibilities for using renewable energy sources are therefore limited, and the draft plan envisages that Slovenia will not increase the use of wood biomass for energy purposes but will even slightly reduce it and encourage a switch to heat pumps and district heating, the ministry replied. Public funds are also used to co-finance the energy renovation of buildings. However, the revision of the Slovenian Operational Programme for Pollution Control, which is still in the process of being adopted, provides a legal basis to regulate priorities and restrictions of fuel use with regard to air quality also at the municipal level.

The European Union is facing a decision: Will we follow the WHO recommendations?

The European Parliament added its amendments to the European Commission’s proposed directive in September, and the European Council commented on the proposal in November, starting the trilogue negotiations.

The European Council did not include additional targets for 2035 in its amendments, which were published online in November, so there is a possibility that they will not be included in the final version of the Directive. This would mean that European legislation would not yet be in line with the WHO recommendations on particulate air pollution when the proposed directive comes into force.

In addition, the European Council’s amendments propose the possibility of postponing the attainment of the air pollution reduction targets for a maximum of 10 years, to 1 January 2040 at the latest. The deferral would be available to countries with a high share of low-income households and a GDP per capita below the EU average, if modelling shows that they will not be able to meet the targets on time. Adjustments to the timetables would also be possible on the basis of challenging climatic conditions and emission sources outside a country’s borders that affect the concentration of pollutants in the air.

Representatives of the three European institutions have met 11 times so far on the new directive, the European Council said in a written response. They stressed that pollutant limit values are among the most politically sensitive issues and will be discussed at a final trialogue meeting scheduled for 20 February this year.

Reducing emissions and concentrations in line with the recommendations and directives will be a major challenge for EU Member States in the future. However, research shows that there is a link between air pollution and mortality even at levels below WHO recommendations. Research has not yet confirmed safe levels of exposure to air pollutants, according to the Lancet Planetary Health journal. This suggests that the health effects of air pollution will be felt in Europe for a long time to come, because even if we meet the recommendations, we will not be able to fully reverse the health effects.

This article on air pollution in Slovenia was created within the European Data Journalism Network (EDJNet), an international project, which is co-financed by the European Commission between April 2023 and March 2025. It was also published on EDJNet’s page.

Nastanek tega članka ste omogočili bralci z donacijami. Podpri Pod črto

Deli zgodbo 0 komentarjev

0 komentarjev