Why doesn’t the Slovenian Financial Administration take action against companies that have not paid taxes in years

In Slovenia, there are around 3,300 companies that currently owe state taxes, but are subsequently avoiding the appropriate insolvency proceedings. Out of aforementioned companies, 2,400 haven’t paid taxes for at least a year and the remaining 1,600, have avoided payment for over two years. The Slovenian Financial Administration is treating these long-term debtors with surprising leniency.

“In this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes,” to famously quote Benjamin Franklin. And, for the majority of citizens and companies within Slovenia, this quote proves to be true. However, this truth does not apply to the thousands of companies which have successfully avoided taxes and insolvency proceedings for a year or more.

According to data published each month by the Financial Administration (FURS), almost 3,300 companies and other legal entities are past due on their taxes for over 3 months, which was notes on the 25 December of last year. Our analysis revealed that two thirds of these companies have consistently owed taxes for the last 12 months and half of them for the last 24 months. Despite accruing long-term debt, not one of these companies filed for bankruptcy, forced settlement, or any additional insolvency proceedings.

Why is the Slovenian government allowing tax debtors to continue on with their business and why does it not appoint bankruptcy or forced collection from these companies? FURS attributes the government’s shortcomings to a lack of human resources, as the financial administration is not capable of collecting taxes from long-term debtors in a more successful and efficient manner.

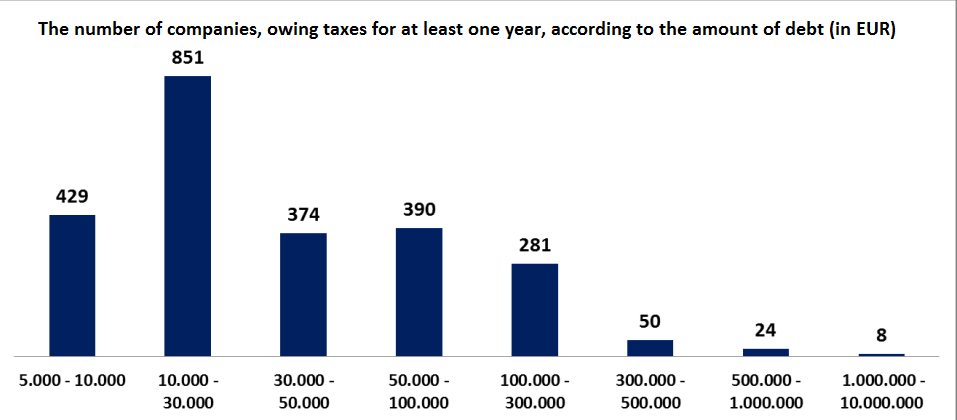

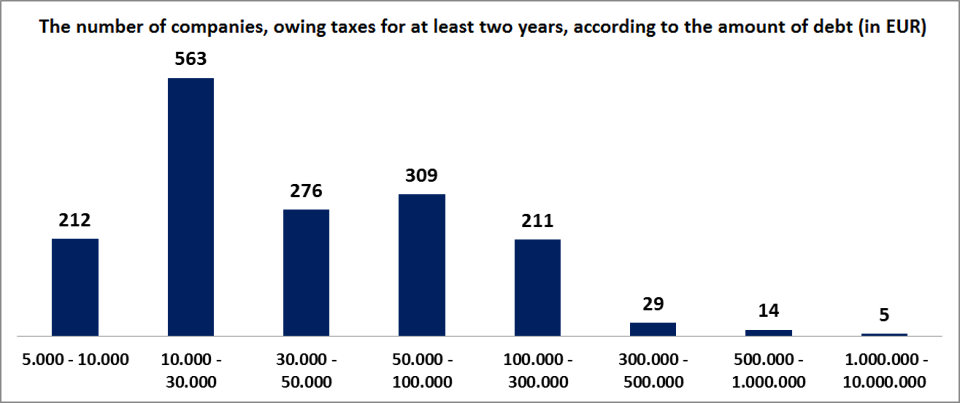

The majority of debtors owe between 10,000 and 30,000 euros

The Financial Administration can boast an additional 500 million Euros in collected taxes compared to last year. According to the information we received from FURS, they collected 13.6 billion in so-called fiscal revenue in 2014. Last year, they collected 14.1 billion. Marta Mihelin, the Director of administration for accounting and enforcement at FURS, told us that their success earned them a compliment from the Minister of Finance.

However, when it comes to tax debt collection, they are not as successful. Last year, the collective debt of all taxpayers, i.e. individuals, companies and sole proprietors, did decrease slightly when compared to 2012, which saw 1.65 billion Euros decrease to 1.42 billion. But as Mihelin points out, this number does not reflect the effort that FURS puts into tax collection. FURS can only collect part of this debt, the so-called “active debt”. Active debt is the debt accrued by companies and individuals that are not involved in any insolvency proceedings. The debt of those who are currently undergoing these proceedings is known as conditionally recoverable debt. FURS cannot actively collect the latter, since repayment has to be assessed as part of bankruptcy or compulsory settlement proceedings.

Between the years 2012 and 2015, active debt decreased from 1.1 billion to 800 million euros. However, this does not mean FURS managed to collect all of this money successfully. Part of the decrease is due to an accounting rule, which states that at the beginning of insolvency proceedings against a tax debtor, the active debt automatically gets treated as conditionally recoverable debt. This type of debt increased from 539 to 623 million Euros between 2012 and 2015. Marta Mihelin estimates that only about five per cent of the conditionally recoverable debt is currently being repaid.

Among the reasons for the amount of active debt and poor repayment practices of conditionally recoverable debt is the low success rate of FURS when it comes to collecting debt as well as late bankruptcy enforcement on tax debtors. Starting in 2013, FURS publishes an on-line list on the 25th of each month of all the companies, which in the past month have owed the state over 5,000 Euros for over three months. While FURS updates this list every month, the archived data is not available. At podcrto.si, we managed to recover this archive of tax debtors dating back up to two years. This allowed us to analyse exactly how many companies have continuously owed taxes to the state in these past two years and also the amount debt of these companies currently owe.

No detailed statistics

On the 25th of December 2015, at least 3,281 companies, which were not involved in any insolvency proceedings at that time, have owed taxes to the state for at least three months. This number does not include natural persons with an activity, such as sole proprietors. Among these, 2,407 companies have owed taxes for at least 12 months. From the latter information, 1,610 have owed taxes for at least 24 months.

We asked FURS exactly which business sectors included the majority of long-term debtors, but as they explained, they do not keep detailed statistics. “In one period, these debtors were from labour-intensive industries. That was a time when production was being shifted abroad. There was one period when many small companies also owed taxes, due to the fact that they were not paid for their services or products. We also have companies working in well-performing sectors, but are in debt because the management made poor financial decisions in the past. Either that or they took on too much credit,” explains Marta Mihelin

Allowing companies to avoid paying taxes for a year or two has various negative consequences. The first results in a lower repayment of debt. The longer it takes FURS to place a company into bankruptcy, or to seize assets in their bank accounts, as well as any existing securities or movable and immovable property, the lower the debt repayment. Their inaction gives the owners time to deplete the company’s assets.

FURS admits to this fact. As they tell us, the majority of companies that are in debt for over three months will never repay. Apart from that, they are still noticing so-called cash transactions, i.e. payments through money orders. With money orders, a tax debtor can bypass their blocked transaction account and transmit the obtained funds to any person with which they have a money order contract. Since the money is not transmitted to the company’s bank account, but is paid directly to a third person or company, FURS cannot seize the money. The debtors are also successfully avoiding the seizure of their money by opening and operating their bank accounts abroad, which FURS is not aware of. Using these methods, the owners can deplete the company’s assets and leave tax collectors with nothing to seize.

Dr Marko Jaklič from the Ljubljana Faculty of Economics criticizes the inactivity of FURS. He believes it is “absolutely abnormal” that FURS allows companies to not pay taxes for over a year and does not subsequently propose bankruptcy after this period. Allowing such practices gives other companies the courage to also not pay taxes, which then “spreads like a cancer among society”. The Tax Administration can hold off bankruptcy for a few months. If it postpones for a longer period, it only encourages “thievery”.

For example, Jaklič mentions Cimos, a company based in Koper, which should have long ago found a suitable owner through the appropriate procedures. But, instead, Cimos is simply being depleted. The company which produces car parts faced trouble due to high credits during the economic crisis and was eventually put on the tax-debtors list in 2014. In May of last year, the court approved a compulsory settlement for Cimos and its long lasting troubles are now being bailed out by the tax-payers. Last year they received 97 Million euros in state aid.

Maintaining employment is not the responsibility of FURS

FURS and the state often use the argument of maintaining employment for workers when it comes to justifying state funded bailouts. For Jaklič, this argument is completely unacceptable. As he stresses, maintaining employment is not their mission, as easing off on tax debtors creates unfair competition for companies that pay their taxes, and consequently have higher business costs. “They are just running away from the inevitable. FURS has to act in time. It is better to close a decrepit company sooner rather than later, otherwise you only prolong the agony of workers,” explains Jaklič.

Why is then FURS so unsuccessful in tax recovery? And why does it not propose bankruptcy, when recovery is unsuccessful? The main reason for this is the lack of human resources, explains Marta Mihelin from FURS.

The procedure for companies that are late in paying taxes is as follows: Eight to fifteen days after a tax obligation matures, FURS sends a warning to the company via email or phone call. According to Ms Mihelin, this strategy is quite successful. Last year, FURS managed to recover additional 210 million euros after a sent reminder. At this stage, FURS may also authorize the payment of debt in instalments, upon request from the debtor. The companies that are repaying debt in instalments are not on the list.

In the case that the tax debtor fails to respond to the reminder, they proceed with the execution on the bank account. FURS then blocks the bank account of the debtor and from that moment on, the bank transmits every transaction into the account directly to FURS. Mihelin claims that FURS usually blocks the bank account of the debtor 15 days after the sent reminder. However, in our analysis, we found several companies that owed taxes for at least three months and their bank accounts still were not blocked. Marta Mihelin has no idea how this could be possible. As she says, tax collectors have clear guidelines on when they should block a bank account.

The recovery procedure gets even more complicated when taking the following steps. If the execution of a bank account is not successful, either because the company avoids this by doing business through money orders or foreign accounts, or because they actually have no income, there are several options. FURS can either seize the company’s monetary assets, or corporate receivables from customers, as well as any securities and movable property they might own. Even if this doesn’t allow for the company to repay its debt, FURS can propose court ordered enforcement of the property.

Enforcements are rare

But FURS does not use enforcement often enough. After blocking the bank account, they can wait for up to a year to see if they can recover any money using the aforementioned methods. They usually decide to seize the assets only after the bank notifies them that there was no cash flow to the company’s bank account in the past 12 months, explains Mihelin.

This means FURS gives tax debtors one whole year to potentially deplete company assets by transferring them over to other companies. In the case of bankruptcy, the liquidator may deny such transactions only for a year from the starting date of declared bankruptcy. Other assets are then lost and thus unable to be obtained by collectors, including FURS. As stated, the majority of companies that have not paid taxes in over three months will never repay their debt.

Why is FURS then delaying the seizure of movable property and other assets belonging to the company? They simply do not have enough employees to carry out such procedures, answers Mihelin. The number of tax debtors, i.e. companies and individuals that owe between 5,000 and 10,000 Euros, is over 18,000, whereas FURS only employs 350 tax collectors altogether. Informing the bank to block an account is a relatively fast and easy task, however, checking which assets are still owned by the company, which could be used to repay the debt, is often a complex and time-consuming task. “We also spend a lot of time on the field. In order to find the debtor at home and to not have him claim the property belongs to someone else. Apart from that, it is almost imperative to have two tax collectors together in the field, so that they can stand as witness for one another and also for safety reasons,” explains Mihelin. In the case of complex executions and those that involve the court, they also need to have a capable lawyer available. At FURS, they are also in lack of the latter.

On the other hand, FURS employees who are dealing with executions “cover” the cost of their salaries, while also generating revenue for the state. In 2015, FURS received 230 million Euros in taxes from such executions. This would mean approximately over 700,000 Euros were collected per tax collector. “I am convinced that with ten additional highly qualified lawyers, we could have received a lot more,” says Mihelin.

Yet, due to the employment restriction mantra in the public sector, any requests for additional employment tends to fall on deaf ears. Last year, after an extended period of time, the Minister of Finance finally allowed FURS to employ an additional 40 people within the entire administration. Yet the fact that over 200 employees have since retired after the merger of the tax and customs administrations, forming FURS, was not considered.

IT Problems

Moreover, FURS continues to have problems with their information system eDIS. At podcrto.si, this issue was already extensively covered: even though the previous tax administration has covered the costs of three quarters of a functional eDIS system, they have received only a third of it. In 2014, the Court of Auditors established that the information system, which was paid for with taxpayers’ money, was overpaid by ten Million Euros. One of the problems with the system was that it integrated poorly with the out-dated one, concerning the external records about the assets of individuals and companies. The auditors’ report stated: “Until February 2014, the Slovenian Tax Administration integrated the renewed information system with only a limited number of internal and external data sources. Therefore, employees working in the fields of tax collection, executions and tax investigation have to get the majority of the data they need for their work through unstructured research across multiple records. In some cases, this process may even require written inquiries to all the banks and savings accounts in Slovenia. This not only burdens the employees, but also represents the risk for delays and thereby affects the success of recovery procedures.” According to Mihelin, eDIS still does not provide adequate connectivity with external records, which causes further delays in executions.

After all other executions fail, FURS can then propose to the court a seizure of the debtor’s property. But, the process of the seizure of immovable property can take up to three years or more. “In the meantime, the debtor might have some cash flow in and they can manage to pay off some of the debt, yet at the same time they ultimately create more. Such cases are the most commonly seen. In cases where the employees do not pay contributions for their workers, we receive letters from these workers, asking us not to propose bankruptcy. The trade unions’ appeal to us not to take action against a company, while the workers at least still have their jobs,” says Mihelin.

The bankruptcy proposals for companies that are unable to repay their debt after a year or two seems like a good choice, considering HR constraints faced by FURS in addition to the sluggish methods of the courts. This would prevent the debtor from depleting the company’s assets and thereby maintain the property in order to repay the debt. The Law regarding financial operations allows tax collectors to propose bankruptcy for any company whose bank account has been continuously blocked for 60 days. FURS usually proposes bankruptcy only after a company has owed taxes continuously for five years, explains Mihelin.

Why wait so long? “Management is required to propose bankruptcy first. We, on the other hand, have to pay an advance first and then prove insolvency. The procedure is then initiated in those cases, where we can asses that we will achieve a more favourable result compared to regular enforcement procedures. This is also to prevent the accumulation of debt,” Mihelin says in defence. However, as stated before, regular enforcement procedures are more or less unsuccessful. Mihelin promises to propose more bankruptcies in the future. By December 2015, the total number of proposed bankruptcies was only 109.

Despite the problems with debt recoveries, not everything is completely bleak, believes Mihelin. Progress can be seen, especially in regards to payments. “We are getting a lot better in this area. I have a feeling that people want order, they would like to have their taxes paid, so I am positively surprised in this regard. There is a lot more of voluntarily paid debt, also because we are more aware. Advertisements and tax registers are raising awareness about tax culture and all this contributes to shifting the mentality of Slovenians when it comes to paying taxes.

Nastanek tega članka ste omogočili bralci z donacijami. Podpri Pod črto

Deli zgodbo 0 komentarjev

0 komentarjev