Heatwaves: global warming threatens more than 100,000 Slovenes

Longer uninterrupted heat periods in Slovenia will be increasingly frequent and intense. The country does not have an integrated strategy to combat climate change yet.

Maintenance work on the roads was accompanied by the tourist peak this year. Cars stopped in the summer jam on the coastal, highland or other Slovenian motorways. In vehicles with switched off engines, the temperature began to rise rapidly, as air conditioning systems were no longer cooling hot air. Some passengers tried to wipe windscreens and protect themselves from the sun. Alongside the cars, road workers were rotating on the roads, which were even hotter than exhausts of powerful machines due to fresh asphalt.

The human body is relatively energy consuming because it produces a lot of heat – especially during heavy physical work. In addition, it can maintain body functions only in a very narrow temperature range, which applies to normal body temperature: about 36.5 degrees Celsius. When the body detects an elevated body temperature, cooling processes are triggered. The heart needs to exhaust warm blood from the inside to the surface of the body, where it cools. This process works normally as long as the individual has a healthy heart and blood vessels; he/she does not have severe respiratory diseases; he/she drinks enough fluid; and there is not too much moisture in the air that would reduce the evaporation of the sweat. Also, it functions while working in an ideal operating temperature range: between 20-22 degrees.

“At 24 degrees, our work capacity is rapidly reduced”, said Martin Kurent from the Clinical Institute of Occupational, Traffic and Sports Medicine at the Ljubljana University Clinical Centre in a professional meeting on safe working in the sun at 24 degrees. At temperatures above 26 degrees, the concentration deteriorates and the physical strength falls. Faults, fatigue and exhaustion begin to emerge, causing more work-related accidents. The body begins to heat rapidly, the body temperature rises to 40-42 degrees and the person experiences a heat load, which can be fatal.

Similar effects have fever in older, cardiac and chronic patients, where the body cannot cool down sufficiently and effectively during resting. Therefore, during heatwaves – longer periods without intermediate cooling – the mortality among vulnerable groups of population is considerably increased.

This danger is not only hypothetical. During the heatwaves in Europe, more than 70,000 people died in 16 European countries in 2005. We also recorded increased mortality in Slovenia, mentioned by Ana Hojs and Simona Perčič in the report about the study on the consequences of heatwaves they prepared at the National Institute of Public Health (NIJZ). “When we reviewed data on deaths by age groups and causes of death, we found that mortality in the period of heatwaves has increased significantly. During these periods, mostly elderly people die, most often because of cardiovascular disease”, the researchers explained. In addition, 137 additional deaths could be attributed to the effects of a heatwave in 2015, an increase of about 7% in relation to expected mortality.

The number of people living in disadvantaged groups is also increasing. According to the NIJZ estimates, there are approximately 120,000 citizens with cardiovascular diseases, which accounts for almost 9 percent of the population aged between 25 and 74 years. According to the Statistical Office, at the beginning of this year, 19.4 percent of citizens aged 65 or more (over 400,000) lived in Slovenia, of which 5.2 percent were over 80 years old (approximately 112,000). This means that there are hundreds of thousands of people affected and threatened by the heatwaves every day. Therefore, Hojs and Perčič are convinced that the heatwaves in Slovenia should be treated as natural disasters, predictable events that will affect a large part of the population and for which systematic preparation is needed, especially in towns.

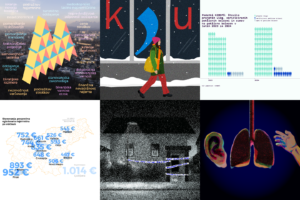

During our research at Pod črto (The Bottom Line), in cooperation with the European Data Journalists Association (EDJNet), we found that the average temperatures in 558 European cities increased significantly compared to the pre-industrial era. The consequences of higher temperatures will also be felt by residents of Slovenian cities, as they can expect more intense extreme weather events, which include heatwaves and floods.

Our investigation regarding the consequences of heatwaves showed that despite the global climate change, Slovenian cities can take several measures that can reduce the effects of higher temperatures. For more comfortable living conditions inside the buildings, efficient energy rehabilitation is needed. The city cools by trees, plants, parks and water surfaces. For outdoor workers, summer workshops need to be adapted to provide work safety. First and foremost, city administrations must accept the fact that heatwaves will become more and more problematic in the future- and start adopting appropriate systemic measures to prevent their negative effects.

Increased Mortality in Cities

Because of the consequences of heatwaves, the city’s residents are most at risk. Cities are warming faster than their surroundings, and their inhabitants are more likely to experience the effects of higher temperatures, which include heatwaves.

European cities are getting hotter, a joint investigation on the warming of European cities, which we have prepared together with European Data Journalists Association (EDJNet), has revealed. We analysed around 560 European cities and found that four cities have already warmed more than 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to the pre-industrial era – a departure from the commitments to the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change. In the investigation, we included Ljubljana and Maribor, which, according to our analysis, warmed up by 1.2 and 0.8 degrees compared with the 20th century.

There are several reasons for the heating of the cities. The first reason is the general rise in temperatures due to climate change.

The Slovenian Environment Agency (EARS) found that the average temperature in Slovenia increased by two degrees from 1961, which is one percentage higher than the global average (The agency used a different methodology than the EDJNet, where it modelled data for urban areas, so the values are not exactly comparable). Recent climate scenarios have predicted that the rise in the air temperature in Slovenia will continue in the 21st century and the size of the increase depends on the greenhouse gas emissions scenarios. According to an optimistic scenario, the temperature will increase by about 1.3 degrees Celsius by the end of the century compared to the 1981-2010 period. It could, however, increase about 2 degrees according to a moderately optimistic scenario and about 4.1 degrees according to a pessimistic scenario.

The temperature rise will greatly increase the heat load in the summer. According to an optimistic scenario, the average number of hot days in Slovenia will increase by approximately 6 days by the end of the century. However, the number of hot days could be about 11 days according to a moderately optimistic scenario, and it could increase to about 27 days according to a pessimistic scenario (Hot days are those with an air temperature exceeding 30 degrees). In all scenarios, the number and duration of heatwaves will increase. In the case of a moderately optimistic scenario, at the end of the century, at least one heatwave will be at least observed annually, which will be comparable to or worse than the heatwave that we had in the summer of 2003.

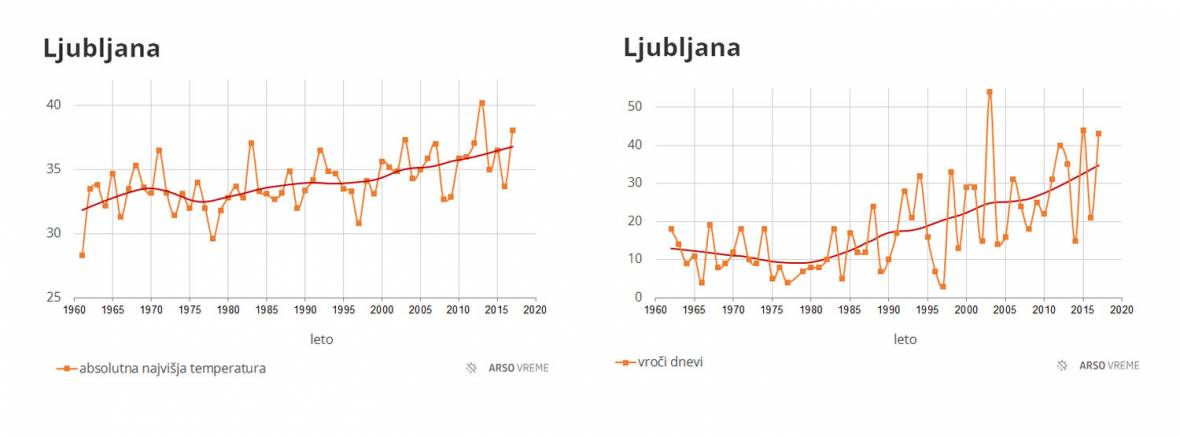

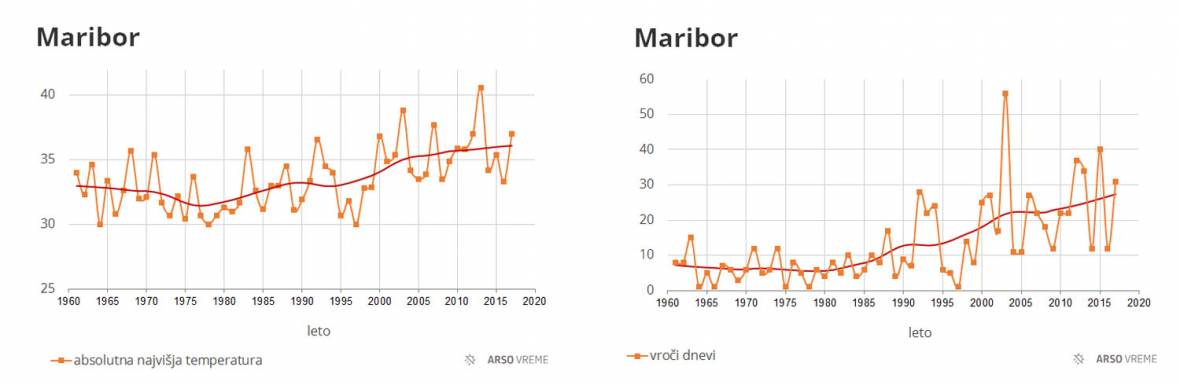

In Ljubljana, the annual average of hot days was around 10 days in the mid-1980s, according to the Mojca Dolinar, climatologist from the ARSO (On hot days, the highest temperature rises above 30 degrees). “Since the mid-1980s, the average has grown steadily, and today we have more than 30 hot days in Ljubljana. The most outstanding is the year 2003, when we had as many as 54 hot days in Ljubljana.

It is very similar to Maribor, but it started with a slightly lower average (8 hot days). The hot days began to multiply in the second half of the eighties and today the average number of hot days in Maribor is around 28. In the same year in Ljubljana, the year 2003 marked a significant departure, when we listed 56 hot days in Maribor. “In Ljubljana and Maribor, the average maximum temperature until the 1990s was around 33 degrees. Then it began to rise mildly and today the average is about 36 degrees. “In both cities, the highest temperature was measured in the summer of 2013, when it exceeded 40 degrees in both Ljubljana and Maribor,” said Dolinar.

Another reason for the warming of cities is the rapid growth of urban environments/areas in the previous century.

In the 20th century, rural residents began to massively migrate to cities, which in the last century also grew by more than ten times. Such a case is Ljubljana, which had approximately 34,000 inhabitants in 1900, and at the beginning of this year, according to the statistical office, there were just under 290,000 inhabitants. Maribor grew more slowly, as it was only slightly smaller than Ljubljana in 1900 (It had about 32,000 inhabitants) and has so far increased to over 105,000 citizens.

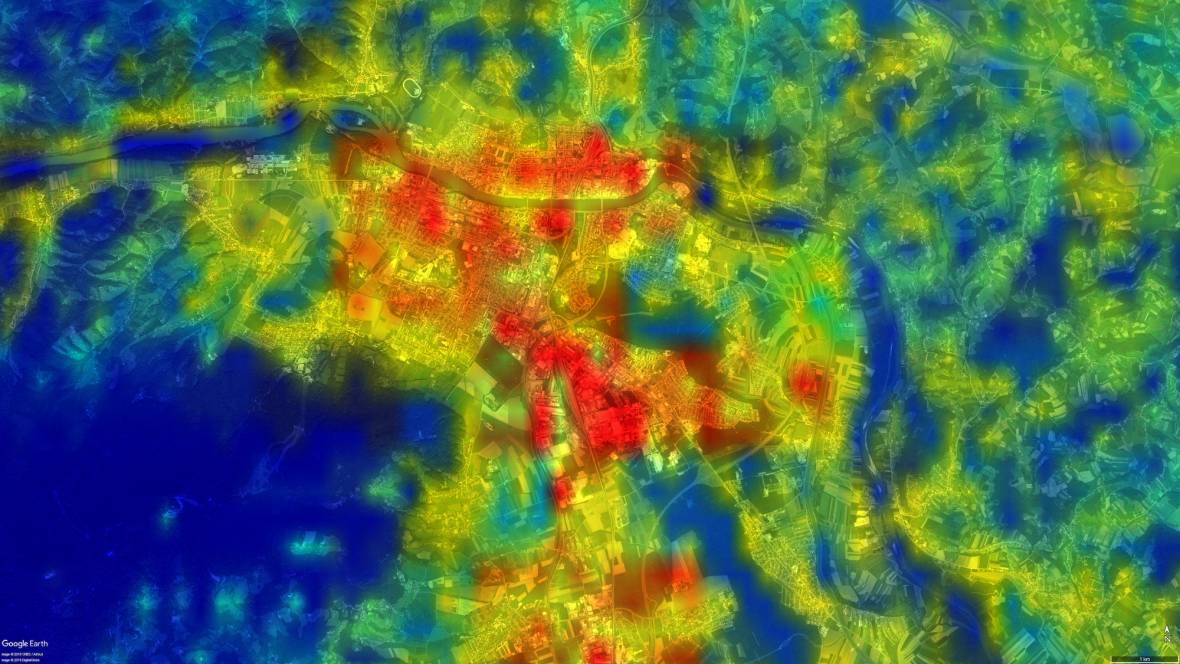

A larger number of residents means more buildings, more built (and less green) surfaces, more infrastructures, more traffic and more energy consumption. All these are the factors that cause the “urban heat island”, which can render cities even warmer than the surrounding area; as Rok Ciglič and Žiga Kokalj from ZRC SAZU, who together with their colleagues prepared a study of the city’s thermal island for Ljubljana, explained to Pod Crto (Under the Line).

In the city, the feeling of the heat perceived by the inhabitants, is not only caused by higher average temperatures, which are triggered by climatology, but also by the stronger heating of built-up areas and infrastructure, emphasized the interlocutor. Asphalt, bricks and concrete absorb sunlight and emit heat to the surroundings – as a kind of large thermal accumulation oven. Due to the high absorptive capacity of the most common building materials, the cities do not cool down at night, which further increases the heat load for the human organism.

“In both Slovenian major cities – in Ljubljana and Maribor – more people died than in the rural areas during the period of heatwaves in 2006-2015,” confirmed Ana Hojs and Simona Percic. This is especially true for older people aged 75 and over. On average, in cities, 58 per 100,000 people died (This is more than expected mortality in this age group) while out of the cities 24 per 100,000 died. This means that the difference between the average death rate in the period of heatwaves between rural and urban areas is 34 per 100,000 inhabitants per year. As a consequence, cities will need to adjust to higher temperatures if they want to reduce the number of heatwave victims that will be more frequent and more intense in the future.

The heatwaves do not only lead to a direct increase in mortality among endangered population groups, but also lower the quality of life, reduce productivity at work and school, and exacerbate chronic conditions. An additional problem is infectious diseases, as their vectors also spread and migrate over latitude and longitude, the interlocutors added. We have been reached by the Zika virus and the West Nile virus, which can be also caught in winter times in urban parks or in green areas. Potable water in the pipes is also being heated and potentially brings new health problems.

But what can cities do at all?

Hot Shopping Centres

The speed and intensity of the warming depends very much on the geographical location, the way of settlement and the size – these are the factors on which the cities do not have much influence. Ljubljana lies in a basin and is relatively poorly aerated due to its location. Maribor lies on a larger river (Drava), which significantly affects the heat exchange and cools the surroundings. The urban climate is not only characterised by differences between the city and its surroundings. Different density of build-up and differences in the level of human activity are also visible within the city itself, explained the geographer and professor at the Faculty of Arts in Maribor, Igor Žiberna. Therefore, rather than the “urban heat island”, we are talking about the city’s thermal arch or the “archipelago”, which is also affected by the weather type and relief type.

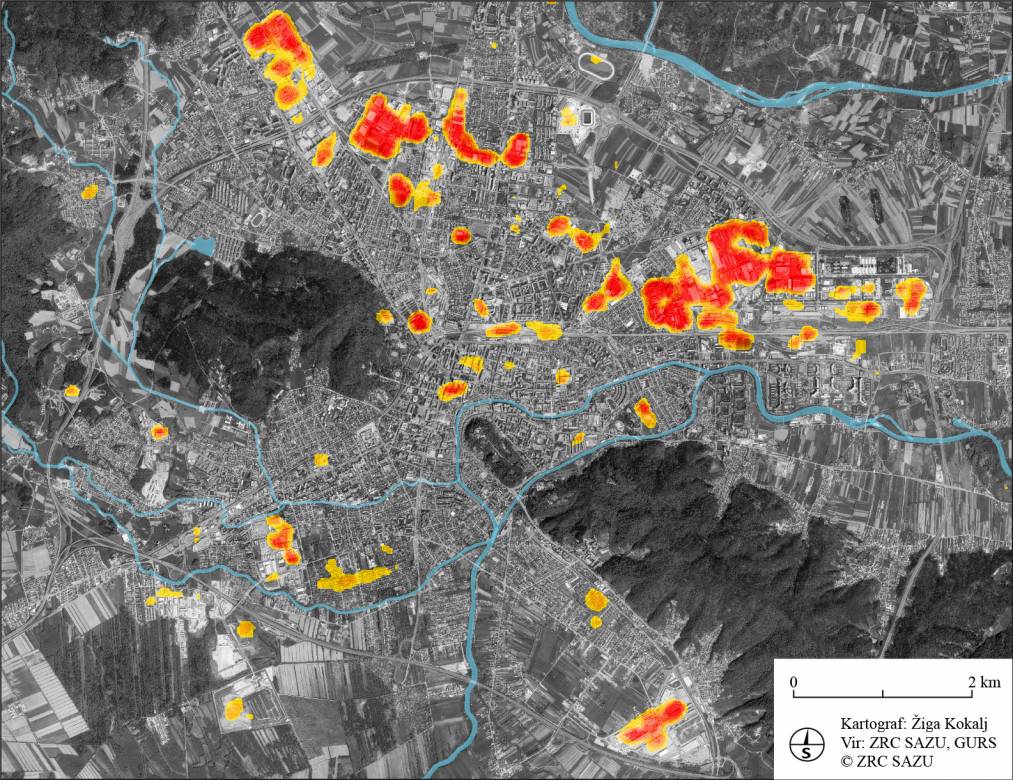

Average temperatures in cities do not measure the effect of the thermal island, since the temperature of the surface – with satellites and planes (heat cameras) or manual measurements at different locations in the city – must be measured to determine the hot spots. For cities, knowing where such thermal islands are located, is very important. With various measures (greening, water surfaces …) in the area of thermal islands, it is possible to limit the feeling of heat and to protect the inhabitants of the whole city from its consequences.

Therefore, Žiberna carried out several measurements in Maribor with which he searched for the core of thermal islands. They are located in the most built-up and traffic busy parts of the city: in the southern (industrial) part of Tezno, in part of the Tabora, in the old city centre, in the Magdalena suburb, and in the industrial part Melja, situated in the area between the bus station and the railway station. His attention was drawn to very hot spots in the Europark shopping centre on the right bank of the Drava River, at service stations and small shopping centres surrounded by larger parking lots.

These concentration areas are similarly noted by his colleagues from Ljubljana. During the preparation of the analysis of the Ljubljana Thermal Island within the framework of the international project UHI, Žiga Kokalj and Rok Ciglič expected that the most important areas of satellite imagery would be industrial areas and the city centre. But they found that in addition to industrial zones, most of the shopping centres are heating up. Researchers have shown that temperatures in shopping centres and in the surrounding areas are up to 5 degrees higher than in other urban areas. Shopping centres BTC, Stegne and Rudnik stand out in Ljubljana. This means that cities should reduce the negative impacts of shopping centres in order to attenuate the effects of the thermal island.

Such findings did not surprise Mihael Sekavčnik, Head of the Department of Energy Engineering at the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering at the Ljubljana Faculty of Mechanical Engineering. Shopping centres are very problematic, as they combine all the factors that increase the warming of urban centres.

“They are surrounded by parking lots, which are large collectors of heat. Their thermal effect is further enhanced by parked cars, which also have high adsorption capacity. An additional problem is the buildings themselves, which must be heated and cooled all the time. Air conditioners are pumping heat from stores and in doing so, they even warm up the environment. The shops are mostly prefabricated buildings, often poorly built and insufficiently isolated”, explained Sekavčnik.

Such persistent hot spots have several negative consequences. They heat up their surroundings, increase their energy consumption and aggravate the heat load for more sensitive population groups – among them older people who have to do their purchases and shop in hot shopping centres. These objects are also problematic because there are many. Several analyses showed that Slovenia ranks above the EU average by number of shopping areas per capita. Municipalities wanted to attract traders and did not prescribe measures for energy efficiency and for the reduction of the impact of the thermal island. If the current hot spots were planted with additional trees, if pavings with planted grass were used instead of asphalt for the parking lots, if the number of parking lots were reduced, if green roofs were manufactured or roofs were repainted with refractory light… such measures would significantly reduce warming and decrease energy consumption, were convinced the interlocutors.

What kind of measures could be taken to tackle problems caused by the heating of cities? The Ljubljana City Municipality (MOL) confirmed that the study on the thermal island warned them of hot spots in large shopping centres. The municipality said that in the framework of the international project on urban heat island UHI, some pilot actions were prepared in the city as examples of mitigation and adaptation to climate change. Among other things, the municipality brought in boats to the fountain in front of the Slovenian Ethnographic Museum, set up a gymnastic house with a green roof in the city centre, set up four “pocket parks” and planted many new trees. It was added that the municipal spatial plan foresees the necessary greening of flat roofs if they exceed a certain area. Similarly, the share of compulsory green areas in terms of land utilisation and compulsory planting of trees, if the parking area exceeds a certain capacity, is also foreseen.

Asked whether they could influence already established shopping centres and require operators to reduce the effects of the thermal island, the representatives of the municipality wrote to the Ministry of the Interior that “there is no adequate legal basis for action on already completed construction, so we cannot impose such behaviour on investors or property owners”. Action is possible during the implementation of individual construction, and the Inspectorate for Environment and Spatial Planning is responsible for it. Some improvements have been introduced in the past years by the shopping centres themselves, said the representatives of the MOL. In the BTC, the renovation of buildings and central control reduced the energy consumption, similarly provided by some of the biggest retailers (Mercator, Spar, Hofer, Lidl …), who are looking for greater energy efficiency when building new facilities.

In addition to the mentioned measures, the MOL was interested in whether the municipality is reviewing the implementation of the spatial plan and requesting changes from traders if their facilities do not meet the requirements. We also asked whether these “pilot actions” and “higher energy efficiency” of the Ljubljana BTC actually reduced the effect of persistent hot spots, which the researchers pointed out. The MOL representatives responded that they did not order additional research. However, they believe that the country should initially adopt a national action plan for adapting to climate change and define the role of cities.

Deficient Energy Remediation

The occurrence of a city thermal island is not limited to shopping centres. In the area of constant hot spots, there are also two city hospitals: the Maribor and Ljubljana University Clinical Centre.

In the infirmary of the Maribor Clinical Centre, medical staff had to provide patients with protective clothing this summer. The heat was too extreme, since the department is located in an old building without isolation and suitable air conditioning. The division of infectious diseases is the most critical department, but it can also be observed that in operational halls it becomes impossible to work under conditions, where ambient temperatures rise above 30 degrees Celsius. “Surgeons squeeze and can get infected if only a drop of a sweat falls on the operative wound of the patient,” describes the situation at a press conference in August Matjaz Vogrin, Expert Director of UKC Maribor.

We learned in Maribor UKC that approximately 60-70 percent of the area has air-conditioning. The biggest problem is the older buildings that do not have proper ventilation and cooling. In addition to the division of infectious diseases, the departments of internal medicine, gynaecology and surgery are critical, where most hospital rooms and clinics are not even cooled down. In the past years, visitors, patients or UKC employees have repeatedly provided portable air conditioners or fans to try to cool down the rooms. Similar scenes could also be observed by patients and observers in other hospitals and health centres, as “no hospital and no health centre in Slovenia has regular air conditioning in all rooms, which certainly affects the outcome of treatment,” criticised Vogrin.

In Maribor, the UKC added that around EUR 1 million would be needed for the overall ventilation of the hospital, but only EUR 190,000 have been allocated for rehabilitation due to poor financial conditions. According to the Director of the Energy Agency for the Podravje region, Vlaste Krmelj, some of the worst symptoms might be eliminated with this money – and with the money collected from the donations, but this would not eliminate any diseases. To adequately combat them, a national and local strategy in energy management would be needed.

Among the most effective measures to reduce the negative effects of global warming, all the interlocutors pointed out to the energy rehabilitation of buildings and to the establishment of information systems for energy management. This means that in the case of public buildings, the controller must first establish an energy accountancy: a precise recording of the consumption of electricity, water consumption and consumption of other energy products for the heating and cooling of the buildings. For public buildings that exceed 250 square meters of useful land, municipalities must, in addition to energy accounting, also implement measures to increase energy efficiency and the use of renewable energy sources while reporting costs, energy use and measures taken at least annually.

If values deviate significantly from the reference values, additional measurements should be made to determine where the losses occur. Sometimes the fault is insufficient isolation or worn out equipment. In this context, work processes are often needed to be improved in order to find out who does not close the radiators and who does not classify and sort laundry in the laundry facilities, which causes unnecessary consumption of water and electricity. Effective energy recovery can significantly reduce energy consumption and, on average, decrease costs by 15-20%, which will return the investment to the operator within five to ten years. It is equally important to improve living conditions and to reduce the heating of urban environments, which could be achieved by successful energy recovery. However, in practice, it is a lot different.

Measures Often Remain Only on Paper

At the Ministry of Infrastructure, we were told that most of the energy in the public sector was spent by hospitals, followed by primary schools, public administration buildings, and buildings for culture and entertainment. The cost of energy products for public buildings is estimated at around 150 million Euros per year.

The ministry estimates that it is possible to save up to 40 or 50 percent of the costs for heating, ventilation, air conditioning and hot water production through a comprehensive energy renovation. Most of the options for improving energy efficiency are in buildings that were built before 1985 (about two thirds). In the context of the allocation of cohesion funds, 63 eligible projects have been selected for co-financing of energy refurbishment with a total value of approximately 42 million Euros, which is expected to save 45,000 MWh per year. From 2016 to 2018, for energy rehabilitation of buildings, a total of more than EUR 90 million out of a total of EUR 147 million non-refundable European funds were available.

Savings are not the only motive for energy recovery, as the country is also bound by the European Energy Efficiency Directive (2012/27/EC), according to which each Member State must renew every year from 1 January 2014 “three percent of the total floor area of the buildings owned and use the narrower public sector that is heated or cooled.” The public sector is also obliged to take into account the Decree on Green Public Procurement (Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia, No. 51/17), which prescribes construction with a smaller impact on the environment and requires saving of natural resources, materials and energy.

Does the State actually achieve these goals? According to the Ministry, the total floor area of the central government buildings amounts to just over 780,000 square meters, which means that, according to the Directive, the State should rebuild more than 23,000 square meters of land (although all areas need not be rehabilitated). However, the renovations in 2014 and 2015 were not implemented due to delays in adopting a long-term strategy to promote energy-renewal investments (DSEPS) and setting up a project office for energy renovation of buildings. Therefore, in 2016 only over 11,000 meter squares of land was renovated by the State. According to the Ministry’s assurances, the prescribed share of the renovation should be captured for the first time by the end of this year. In total, Slovenia has renovated 0.15 percent of the buildings owned and used by the public sector, which, according to the Ministry, reaches the EU average. However, this is by far less than 3 percent per year, as prescribed by the European Directive.

Delays in enforcing the Directive are not the only problem. For an efficient energy strategy, it is first necessary to determine which buildings are most wasteful and what kind of rehabilitation would be most appropriate. However, the problems begin with the data acquisition, said Vlasta Krmelj, Director of the Energy Agency for Podravje.

About 250 public buildings in 25 Podravina municipalities are monitored by the Podravina Agency. A good quarter of the buildings were energetically rehabilitated, while others managed partial renovations or left them in their original condition, said Krmelj.

For these buildings, the Agency monitored monthly electricity and water consumption and heating costs. Among other things, it has been observed that the consumption of electricity for heating is decreasing, while cooling costs are increasing – despite the fact that public buildings are less burdened during the summer months. It was also found that the winter is less cold, when the buildings need to be heated over the weekend, so that the rooms are warm enough on Monday, which is consistent with the forecasts of the EARS. For a more detailed analysis of the performance of buildings and better adaptation to climate change, systems for daily data capture would be needed, but the Agency cannot afford such a solution financially.

Without quality data, it is not possible to accurately estimate what remediation would bring the most money and energy savings, explained Krmelj. Municipalities are obliged to prepare a local energy concept and to report to the state whose energy efficiency measures are implemented, but too often these remain only on paper. Only a year ago, the State introduced a special electronic portal and enforced electronic reporting rules, which will check the implementation of the local energy concept. It still did not adopt the national energy concept – a basic strategic document that would guide the energy policy of municipalities.

In Slovenia, too many energy remedies are highlighted during campaigning – because the municipality has acquired dedicated European cohesion funds when the mayor wants to boast a renovated school or kindergarten, or because suppliers are aggressively selling and providing them the current modern solutions: gas, biomass, solar energy or heat pumps according to what they have written in the local energy concept.

“Many municipalities have commissioned the creation of a local concept only to enable it to be shown to the inspectors if they visit them casually. Then they put it back in the drawer.” critically commented the woman director.

Such campaigning or incomplete remediation can bring more costs than savings. There are also frequent cases where the municipality finds money for remediation, but not for the education of janitors and staff. “We recently renovated one of the Maribor gymnasiums, replaced the windows and arranged everything else, and the costs were increasing. How come? Energy cost did not go up so much; all the work was done according to plans … Until we found out that the setup of new devices was wrong.”

The same applies to the Maribor hospital. “Already since 2008, we know that our UKC has problems with the climate change. Probably there are no residents of Maribor or the surrounding area who would never lie in the hospital room or come to visit and see how terrible the situation can be in the summer. Rehabilitation is necessary, but it must be comprehensive. If they set up local ventilation systems in the rooms that will blow too much or too little, they will not be able to remote control, which will be loud and will contribute to the warming of the environment, then they will not improve the conditions for work and living conditions despite the investment,” Krmelj pointed out. She added that the energy rehabilitation of objects is only one piece of the puzzle among measures to reduce the temperature in cities.

Cooling of the rooms will not help if their surroundings will not cool down. This means that much more active interventions are needed in the urban area.

Greenery Cools Down the Most

What kind of interventions are these? Žiga Kokalj, Rok Ciglič and Igor Žiberna told us that in addition to the hot spots, cooler areas are also very pronounced.

The Ljubljana castle is an example of a built-up space, but it is much colder than the comparable facility in the city because of its height, surrounding forest and better ventilation. In Maribor, the lowest temperatures were measured in areas with lower relative heights and natural vegetation: in urban parks and lowlands in the old riverbed of the Drava, which is covered with forest and meadows. On satellite imagery, the differences between the senile and the sedentary locations, the cooling effect of the lighter or green roofs, and especially the avenues, parks and green areas, and the water surfaces, such as rivers or ponds, can be clearly seen.

However, establishing green areas does not just mean planting new trees.

The claim that green and water surfaces mitigate the consequences of heatwaves and cool down the city is definitely true, Mihael Jožef Toman from the Biotechnical Faculty confirmed to us. “However, we want to transfer too many parts of nature to the city, rather than the entire system that falls next to it. The tree cannot stand-alone or live in a kind of concrete flower sweat, which we often see in cities. The tree is part of a forest ecosystem or coalesces with grassland. The same is valid for ponds and artificial lakes. They are influenced by natural processes. They will be swollen, bloomed; the water will be disturbed and dampened. Perhaps they will cool down somewhat, but they will multiply bacteria and other pathogens and cause more harm than good. There will be nothing left that you have built, planted or drawn on a computer. Every built nature must be maintained all the time, which urban planners are not aware of enough.”

Maja Simoneti, a landscape architect and project manager at the Institute for Spatial Policy, who has a doctorate on the topic of regulating public green spaces, is also reminded of the integrated urban planning. She said that planting trees, regulating green areas and parks has never been only one purpose – for example, to reduce the consequences of heatwaves in the city. “Since the beginning of industrial cities, green areas – parks, gardens, promenades and greens – have many different roles. Parks did not only create a pleasant climate and better image of the city, but they also provided for the well-being and connection of the citizens, as they were a place to meet and spend their free time,” explained Simoneti.

Therefore, in the modern planning of public green areas, multifunctionality is of great importance – in biodiversity design (planting of different compatible plant species), suitable trees are selected (water consumption, resistance to pests …) and water circulation is allowed (We do not water the trees with asphalt or pavings almost to the trunk). Unfortunately, such sustainable solutions were not promoted by the local urban policy, but these ideas came to Slovenia mainly due to European projects – when such projects started to receive funding from the European Union, she added. On the one hand, this was positive, as city administrations began to take interest in and implement environmental projects. On the other hand, cities often fulfilled project criteria rather than thinking comprehensively about the importance of green spaces in their environment.

This is reflected, among other things, by the recent renovation of Gosposvetska road in Ljubljana, said Simoneti. “Many solutions are good. More space was allocated to pedestrians and cyclists. When it came to planting new trees, hop-hornbeam (ostrya carpinifolia) was chosen – not some exotic decorative trees. At the same time, it was not envisaged to add a rainwater catchment system to the trees, but it was thought they should be watered. Perhaps, it would have been wiser to opt for the option of tree plantation with different species instead of a tree with one species of trees, which would increase biodiversity while raising resistance to climate change and pests.”

Michael Jozef Toman also saw the same shortcomings. “Hornbeams grow very slowly and will not give a serious shadow for a long time. Monoculture is less resistant to pests; trees do not have almost any room for the development of the root system at the trunk, which will significantly reduce their photosynthetic and cooling potentials. There will also be very limited possibilities for discharging water at the high tide, which has no place to run away. It is a shame, because instead of a functional nature in the city we have another system of tree flower pots that will have to be watered and will not have the desired cooling effect.”

Despite these criticisms and recommendations, the interlocutors agreed that the design of green areas is more professional than in the past. The city administration is increasingly aware of the importance of co-operation in the planning of public green spaces, and the Director of the Ljubljana Botanical Garden, Jože Bavcon, was also optimistic. During the preparation of projects, contractors do not consult only with builders and landscape architects.

“We are more and more frequently asked about whether the proposed plant species are suitable for Ljubljana. At the recent renovation of the Slovenska and Gosposvetska roads, we took into account the fact that instead of the original ornamental trees we proposed the cross selection: flowering ash (fraxinus ornus), hop hornbeam (ostrya carpinifolia) and whitebeam (sorbus aria), which is interesting for bees and hence for urban beekeepers,” said Bavcon.

The MOL has listed several projects that have a positive influence on the cooling of the city and they take into account the principle of multifunctionality of public green spaces. About 40,000 trees have been planted in the last twelve years. Some degraded urban areas have been redeveloped to new green public areas (Rakova jelša park, Vodnikova cesta park, Koseški bajer park, Teren Park and Moste family park). In the parks Tivoli, Rožnik and Šišenski hrib, various measures are planned to conserve biodiversity, maintain Tivolski bajer and take care of the preservation of autochthonous animal and plant species. They also launched a campaign in which the townspeople are encouraged to plant indigenous native plants on the balconies (donating them seedlings), thus enriching the environment and allowing foraging to bees.

Despite positive changes, the Director of the Botanical Garden sometimes faces surprises with some sort of clumsiness. “Some time ago, they called us asking why the young trees at the Slovenian and Gosposvetski were dry, although they were watered with recommended 200 liters of water per week. Finally, we found out that maintenance workers blended all the water at one time, instead of distributing it throughout the week, and considering that, the soil is freshly dredged and porous as a result of construction work. That is why all the water was stuck along the roots, and the trees were thirsty”, Bavcon smiled.

Cities without a Comprehensive Strategy

During the investigation of the effects of heatwaves on the inhabitants of the two largest cities in Slovenia, we found in several cases that the decision makers had no overview of the whole picture. Higher temperatures affect, inter alia, public health, transport, urban planning, energy policy, education, work efficiency, occupational safety and the spread of invasive plants. But cities do not have a uniform strategy to prevent the negative consequences of environmental change that would connect all involved professions and public services. Therefore, too many partial, reckless or insufficiently effective solutions have been introduced too many times.

“Trees should be everywhere because the population is old. It would be ideal if the all the city roads were made so that townspeople could walk in the shade – visit the offices, make purchases, and go to the city park before the heat hits. Instead, on the Tivoli, almost all the walking trails have been routed so that you are constantly in the sun all the time. There are no trees on the roads that would throw a shadow”, said Jože Bavcon.

Trees are also missing along the roads. Driving through the avenue almost instantly reduces temperature in the car even up to 6 degrees, Bavcon explained. But along the roads, almost no trees are planted any more, or we even recklessly cut down those that were planted by our ancestors during the time of horseback riding. Despite the fact that these trees today will significantly mitigate the summer heat load on the road, indirectly reduce the number of road accidents, as well as protect workers to keep themselves cool during the maintenance of the road in the summer sun…

These construction sites, rooftops and roads generally have no protection from the sun and heat, said Tanja Udrih Lazarus from the Clinical Institute of Occupational, Traffic and Sports Medicine, which last year and this year led the campaign Safe work in the sun. They do not have suitable protective clothing, the building sites are not shaded, employers do not adjust their working hours so that workers can at least get cooling during the day. Also, because the legislation and supervision in this area are too loose, said Udrih Lazar.

The Occupational Health and Safety Act stipulates that the temperature in the work areas must not exceed 28 degrees. For those who work outside, however, employers must “protect themselves from adverse weather”, which, despite numerous health warnings and instructions from work inspections, often do not include heat.

At the Ljubljana and Maribor city administrations, we were assured that protective measures are applied to employees in the public services: adapting workers to summer heat, providing protective clothing and water to workers, and allowing them to go to the air-conditioned rooms. How are these workers, who perform works in these cities by order of the municipality, protected? That is what we asked the labour inspection. They told us that ‘data on workers’ aimed at protecting workers allows for monitoring of the consequences of heat for workers. The consequences are observed at the Ljubljana Urgency and in health centres, because the urgent need for help during heatwaves is more often solicited by workers who work all day in the sun – because of a heat stroke and other complications that are a direct consequence of the heat.

There is also little care for the elderly and patients who, according to urgency and health care homes, are also the frequent seekers of urgent health care during heatwaves.

Ana Hojs and Simona Perčič said that the consequences of heatwaves in cities could be considerably mitigated by some relatively simple measures. An increasing number of media have been contacted by the NIJZ and ARSO during heatwaves to protect citizens against heat, and to be made aware of these measures. Such publicity is very important, as more and more people follow the most important instructions: avoiding the sun and physical work, drinking enough and staying in chilled areas. Cities are less successful in systematic monitoring and warning of chronic patients and the planning of additional health facilities in hospitals and health centres during heatwaves.

We also know very little about the elderly and socially deprived individuals, the researchers warned. Their study of the consequences of heatwaves showed that the elderly is extremely exposed (often poorer), who live alone and cannot provide adequate living environment (install air conditioners). The Eco Fund, however, reimburses the cost of the investment in the energy rehabilitation of the building to those floor owners who receive regular social assistance. Cities do not yet have special programs to help the elderly and socially endangered citizens, who cannot receive subsidies for the purchase of air conditioners, the representatives of the two largest city municipalities replied.

Additional public health problems are caused by the planting of tree species that blossom and make life miserable for allergy sufferers, added Hoys and Percic. And this is another overlooked natural phenomenon, which will be influenced by higher temperatures.

Integration, Incentives and Control

Due to higher temperatures, hot waves will also become a serious public health problem in Slovenia, as hundreds of thousands of vulnerable populations will be directly affected in the coming decades: older, chronic and outdoor workers. Although temperature rises are a global phenomenon, on which individual (especially small) state does not have much influence, cities have more effective measures to reduce the consequences of heat, in particular by planning green and water surfaces and by achieving energy renovation of buildings. But only if the solutions are not only cosmetic, since the individual tree, green roof or “pilot action” cannot eliminate the consequences of wrong spatial decisions (hot shopping centres, new parking lots …) or a lack of national energy policy.

Cities must be adapted to higher temperatures all over the world. In Singapore, there are trees and gardens in the architecture of buildings. In Australia, the United States and other countries, large- scale dyeing projects have been prepared, as the reflective white colour can reduce the temperature in the building by a few degrees and decrease energy consumption due to air conditioning. In the Middle East and China, cities build wind and water towers, set up large shades, and construct pools and artificial lakes.

We also found some good practices in Slovenia. The MOL has introduced energy accounting for 250 facilities (of around one thousand) managed by the municipality, and the effects of energy renovation are monitored on the rehabilitated facilities by the central control system (65 buildings were rehabilitated; energy savings are estimated at 30 percent). The interlocutors agreed that more and more cities and municipalities are increasingly taking into account different disciplines in the renovation of streets or public buildings: they consult with landscape architects, order energy studies and strive for biodiversity and multi-purpose public green spaces. They also congratulated the awarding of energy managers’ prizes, for which municipal officials and other civil servants have been successful in recent years.

Such incentives are very effective, says the Director of the Podravina Energy Agency Vlasta Krmelj. In Austria, the federal government offered prizes worth thousands of Euros to each municipality, which provides the government with the project documentation for the construction and renovation of a low-energy public building. “It does not sound a lot,” said the Krmelj. “But the municipalities are still competing for this money, because it is very easy to get, and the state gives them a professional overview of the documentation while proposing improvements. The municipality gets free advice, and the State can actively influence the implementation of the national energy strategy.”

Systemic incentives similar to those in Austria are too small in Slovenia. Two years ago, the government adopted a strategic framework for adapting to climate change and set up an interdepartmental working group led by the Ministry of the Environment and Spatial Planning. The group is currently only engaged in the preparation of research and long-term climate scenarios, which should then provide a “basis for implementing legislation that is relevant to adapting to the effects of climate change”. Slovenia has also not prepared a national energy strategy. At the Ministry of Infrastructure, the officials are preparing a basic development document in the field of energy (Energy Concept of Slovenia), with which they want to set goals for “reliable, sustainable and competitive energy supply for the next 20 years.” However, the Ministry announced that the Resolution on the Energy Concept of Slovenia would most likely be adopted only at the end of the next year.

Good practices were therefore not brought about by national policies, but by changes in the European budget and European projects that were acquired by some municipalities. Each municipality separately depends on how – and if at all – it will respond to environmental changes. But that is not enough. The municipal administrations did not have clear and above all binding guidelines on how to manage energy and how to measure the effects of given energy and technology choices, how to mitigate the consequences of higher temperatures and how to prepare for climate change. Consequently, the State did not have an active influence on the urban energy policy at the local level and did not monitor how well the money was used for the energy rehabilitation of public buildings; what were the effects of the rehabilitation and how much savings were achieved.

In order to effectively reduce the consequences of global warming, a holistic plan is therefore crucial. This plan is supposed to be a national energy strategy, which the government is expected to adopt by the end of the next year. Only then can the actual implementation of these measures be fulfilled. Any new delay is unacceptable, as the consequences will be strongly felt by citizens in the future. Especially if the country does not succeed in implementing the new strategy effectively.

Original Source: https://podcrto.si/vrocinski-valovi-globalno-segrevanje-ogroza-vec-100-000-slovencev/

Nastanek tega članka ste omogočili bralci z donacijami. Podpri Pod črto

Deli zgodbo 0 komentarjev

0 komentarjev